Picture this: You’re an orthodontist, standing in your clinic, ready to battle malocclusions like a dental superhero. Your trusty sidekicks? Brackets, bands, and auxiliaries. But then, lurking in the shadows of enamel comes a formidable foe—Molar-Incisor Hypomineralization (MIH). Cue dramatic music.

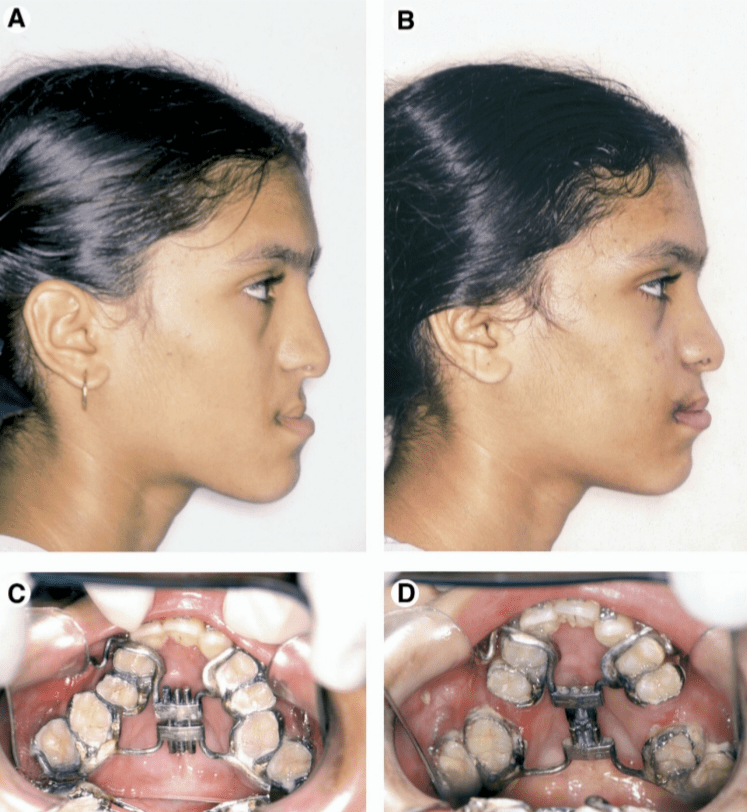

(A and B) Demarcated opacities (hypoplasia) in enamel of molars. (C and D) Opacities on the occlusal surface and posteruptive breakdown of molars. (E to H) Atypical composite restoration involving the occlusal restorations in molars.

Now, you might be thinking, “Really? Another dental complication? Didn’t we already have enough to deal with—like convincing teenagers to wear their rubber bands?” But fear not! We can break down this orthodontic enigma using Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle method. Yes, the same framework that inspires businesses and leaders can also help us decode MIH. Let’s dive in.

The “Why” – Our Core Purpose: Why Should We Care About MIH?

If you’re an orthodontist, MIH isn’t just another acronym to add to your vocabulary—it’s a genuine clinical headache. This condition, which disrupts enamel development, makes teeth more porous, fragile, and annoyingly prone to decay. Imagine trying to bond brackets to enamel that crumbles like a poorly baked cookie. Not fun.

Beyond the technical struggles, there’s the human factor. Kids with MIH often experience dental anxiety, sensitivity, and a higher risk of caries, making their orthodontic journey more challenging. As professionals dedicated to crafting beautiful, functional smiles, we need to take MIH seriously. Because at the end of the day, what’s the point of straightening teeth if they don’t last?

The “What” – Understanding the Beast: What Is MIH Exactly?

MIH affects the first permanent molars and incisors, leading to weak enamel that flakes, fractures, and generally behaves like it skipped calcium class. Researchers blame a mix of genetic and environmental factors, including childhood illnesses, antibiotics, and—because why not?—potentially some mysterious, yet-to-be-determined causes.

Orthodontists face a tough battle here. Hypomineralized enamel doesn’t bond well, meaning brackets are more likely to pop off mid-treatment, like an overenthusiastic popcorn kernel. Sealants and fillings? They don’t always stay put. In severe cases, extractions may even be necessary, often under general anesthesia. Add in the stress of anxious kids, frustrated parents, and mounting healthcare costs, and MIH turns into more than just an enamel issue—it’s a full-blown orthodontic challenge.

The “How” – Fighting Back: How Can We Manage MIH in Orthodontics?

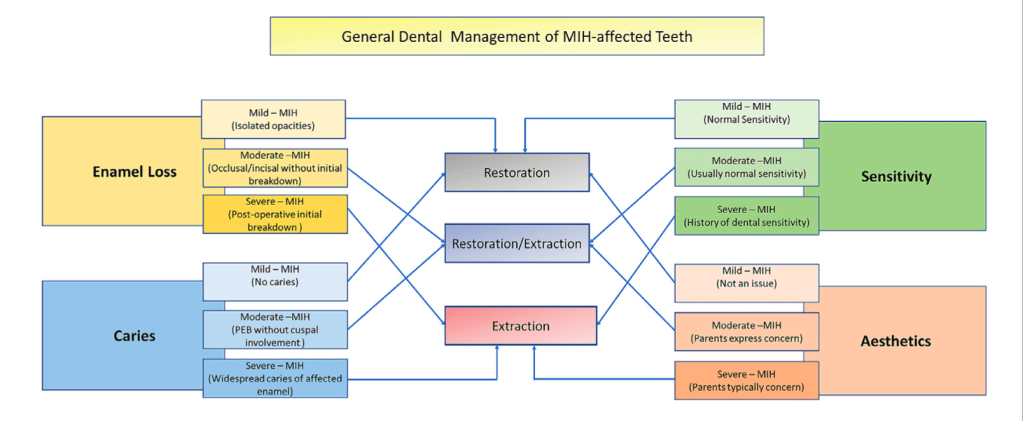

Here’s where we get creative. Since MIH-affected teeth can be hypersensitive and structurally compromised, orthodontists need to tweak their usual strategies. Some battle-tested tips include:

- Stronger Bonding Protocols: Think of it like using super glue instead of tape. Resin-modified glass ionomers or self-etching primers may offer better adhesion.

- Adjunctive Support: Don’t just slap on a bracket and hope for the best. Consider bands, indirect bonding, or even temporary anchorage devices to minimize stress on hypomineralized teeth.

- Strategic Treatment Planning: Sometimes, it’s better to extract a compromised first permanent molar early to allow for favorable space closure—sort of like cutting your losses before they spiral out of control.

- Desensitization Strategies: MIH teeth can be dramatically hypersensitive, making simple treatments feel like medieval torture. Pre-treatment fluoride varnishes, casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP), or desensitizing agents may be game changers.

- Multidisciplinary Collaboration: Since MIH is a complex condition, working closely with pediatric dentists and restorative specialists ensures comprehensive care. Translation: Teamwork makes the dream work.

How Do We Measure MIH Severity?

Great question! Over the years, researchers have tried to classify MIH using complex scoring systems. Some use criteria like:

- Demarcated opacities – The ‘Instagram filters’ of enamel defects.

- Posteruptive enamel breakdown (PEB) – The ‘oops, it’s crumbling’ stage.

- Atypical restorations – The ‘let’s fix this mess’ approach.

- Tooth extractions due to MIH – The ‘eviction notice’ for first permanent molars.

- Failure of eruption – Because sometimes, teeth just don’t feel like showing up.

One commonly used scoring system is the MIH Treatment Need Index, which, let’s be real, sounds like something straight out of a bureaucratic nightmare. But it’s actually useful—it helps us determine how bad the MIH situation is and what to do next.

Does MIH Affect Quality of Life? Oh, Absolutely.

If you think MIH is just about funny-looking enamel, think again. Studies show that MIH can significantly impact a child’s oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). Here’s how:

- Oral Symptoms & Functionality: MIH-affected molars are often hypersensitive, making eating ice cream a horror movie experience.

- Social & Emotional Impact: MIH-affected incisors can make kids feel self-conscious about their smiles, leading to social anxiety. And let’s not forget about potential teasing—because kids can be brutally honest.

- Increased Dental Fear & Anxiety (DFA): Some studies say MIH-affected kids are more likely to dread dental visits. Others say, “Nah, they’re fine.” Either way, behavior management is key.

So, What’s the Game Plan?

MIH doesn’t come with a ‘one-size-fits-all’ treatment. Instead, it requires a mix of strategies:

- Minimally invasive techniques (like microabrasion or infiltration) to improve aesthetics.

- Restorations to protect those weak spots—composite resins, glass ionomer cements, and the occasional crown for stubborn cases.

- Fluoride varnishes and desensitizing agents to ease the ouch factor.

- Extraction of molars (if necessary) with careful ortho planning—because no one wants unexpected space issues later.

- Patient and caregiver education (because sometimes, a little reassurance goes a long way!).

Step 1: To Extract or Not to Extract?

Before anything else, orthodontists must decide whether the MIH-affected teeth should stay or go. If the teeth are beyond repair—hypersensitive, structurally weak, or just outright stubborn—it may be best to bid them farewell. If they are salvageable, then buckle up because they require extra TLC during treatment.

Bonding and Banding: Special Considerations for MIH-affected Teeth

MIH-affected enamel is like a fragile antique—handle with care. Unlike their healthier neighbors, these teeth don’t always cooperate with traditional bonding and banding techniques. But don’t worry, science has our backs! Here’s how we can secure brackets and bands without a meltdown (from either the patient or the orthodontist).

Orthodontic Bonding Tips:

🦷 Prophylaxis First: Clean the tooth surface with a rubber cup and fluoride paste (up to 13,500 PPM fluoride). Think of it as a spa day for the tooth before the real work begins.

🦷 Pretreatment Magic: A little 5% sodium hypochlorite works wonders before using a self-etching primer bonding system. It’s like priming a wall before painting—essential for a strong hold.

Cementing and Bonding Options:

🔹 GIC (Glass Ionomer Cement): A reliable option with fluoride release—because extra protection is always a plus.

🔹 RMGIC (Resin-Modified GIC): Think of this as GIC with superpowers—it has better adhesion and longevity.

🔹 Compomer (Polyacid-modified GIC): A hybrid option that offers flexibility and durability.

🔹 Resin Composite: The go-to for a strong, lasting bond, but only if the enamel allows it. MIH teeth can be temperamental!

Banding Done Right:

📌 Metal Printed Bands: Custom-fitted for a snug, secure grip. Think of it as a tailored suit—because one size never fits all.

Utilization of extraction spaces for orthodontic corrections

Ah, the noble First Permanent Molar (FPM)—a tooth that stands its ground, anchors the jaw, and chews through life’s challenges. But what happens when it’s compromised beyond repair? Orthodontists face a real conundrum: extract it and risk space management issues, or keep it and endure the long-term consequences? Let’s break it down (pun intended) with a deep dive into extraction spaces for orthodontic corrections, all while keeping our humor intact—because nothing soothes dental woes like a good laugh!

Orthodontists typically avoid extracting FPMs because of their strong anchorage potential. Think of them as the wise elders of the dental arch, holding everything together. But when they fall victim to hypomineralization, decay, or pain, tough choices must be made.

Timing is everything! Extract too early, and adjacent teeth tip into the space like an overly enthusiastic Jenga tower. Extract too late, and you risk poor occlusal contact, overeruption of opposing teeth, and the orthodontist giving you “that look.”

The Referral Chain Reaction

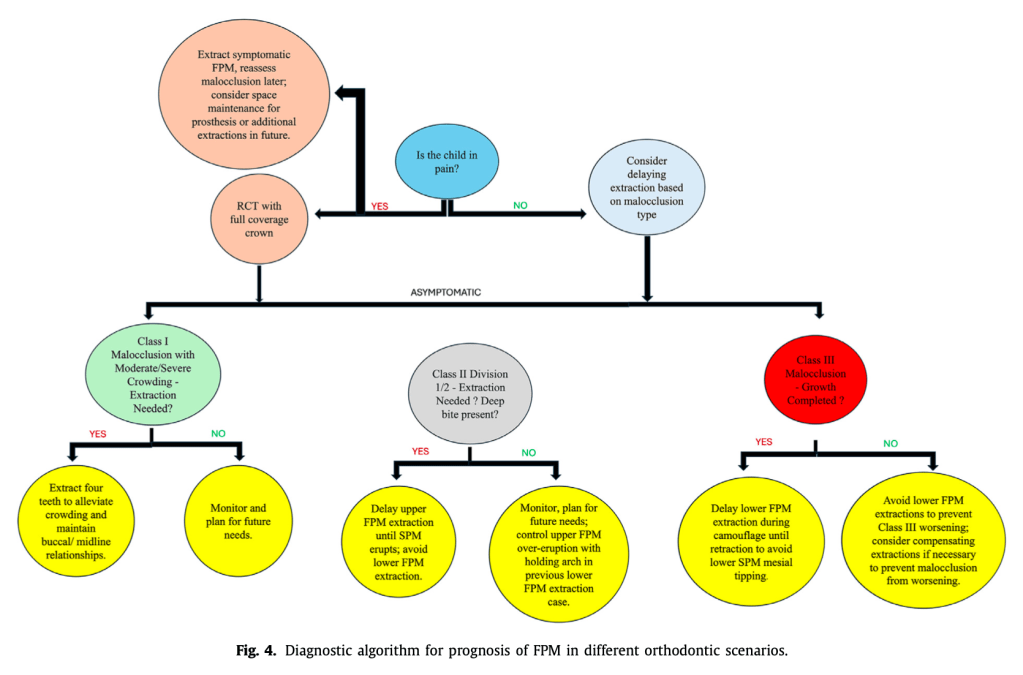

Most patients first visit their general dentist, who then passes the case to a pediatric dentist. If the situation is dire, the orthodontist enters the scene, often finding themselves in a borderline decision-making scenario. At around 8-9 years old, kids undergo assessment, as this is the sweet spot where Second Permanent Molars (SPMs) are still in development. Severe pain? Extraction is likely, no matter the malocclusion type.

Timing Matters: Extracting the Lower FPM

Extracting a compromised lower FPM while the SPM is still developing (between ages 8-10) minimizes occlusion disruption. But miss this window, and you may be dealing with tipping, rotation, and spacing nightmares. Think of it like catching a bus—you don’t want to be too early or too late unless you enjoy waiting at the stop forever.

However, once extracted, the domino effect begins. Patients may face mesial tipping of upper and lower SPMs, distal migration of premolars, and bite deepening. Orthodontists must then break the news: “Congrats! You might need future extractions and prosthetic work.” Sounds fun, right?

The Third Molar Wild Card

If there’s a third molar in the same quadrant, hooray! Space closure improves. If not, no biggie—patients can still function with a shorter dental arch. It just makes mesial movement of the lower SPM a tad more complicated.

The Art of Extraction Strategy: Class I, II, and III Cases

- Class I Malocclusion (Moderate to Severe Crowding): Extracting FPMs can create much-needed space, but it’s often best to wait until the SPMs erupt. If extractions aren’t needed, stainless steel crowns may be the unsung heroes of long-term FPM protection.

- Class II Division 1: Delayed extractions of upper FPMs help avoid mesial drift, which could mess up overjet correction. In cases of a retrusive mandible, keeping lower FPMs intact is preferred—because excessive retraction can lead to airway complications. Nobody wants that.

- Class II Division 2 (Deep Overbite Patients): Lower FPM extractions? Bad idea—especially for brachyfacial cases. Instead, retention strategies and immediate appliance placement post-SPM eruption can help maintain vertical dimension.

- Class III Malocclusions: Super unpredictable growth patterns mean extractions should be postponed until growth ceases. Removing lower FPMs can worsen the situation, making upper third molars redundant and worsening reverse overjet. In short, let the teeth settle before making any rash decisions!

The Dilemma of Restoring vs. Extracting FPMs

Endodontic treatment sounds like a noble plan, but reality hits hard. The success rate of restoring hypomineralized teeth is dicey at best. Bond failures, post-eruptive breakdown, and the need for perfect sealing make restorations a gamble. Plus, getting an 8-year-old to sit still for a lengthy procedure? Good luck! If the initial restoration fails, a second round of general anesthesia might be needed for extraction—something everyone would rather avoid.

Space Closure & The Battle Against Overeruption

If the lower FPM is extracted before functional therapy, maintaining occlusal coverage is crucial. Overeruption can be a real nuisance, and a holding appliance might be necessary until the space is restored prosthetically or closed via orthodontic treatment. But compensating extractions? Only in extreme cases where the FPMs are beyond salvation!

The Final Takeaway: The Art (and Science) of Extraction Timing

Managing space closure is no walk in the park, especially in deep curve of Spee cases or patients with reduced lower anterior facial height. Add strong occlusal forces into the mix, and even stainless steel crowns struggle to stay put.

Class III cases demand the most caution, as premature extractions can throw everything out of whack. The best approach? Delay major decisions until growth stabilizes and all options (including orthodontic camouflage vs. surgery) are on the table.

Orthodontists are basically playing 4D chess when deciding whether to extract an FPM. It’s all about precision, timing, and making sure one move doesn’t throw the whole game into chaos.

So next time your orthodontist suggests extracting an FPM, know that they’ve calculated the risks, assessed the potential consequences, and likely lost sleep over it. Because in the world of orthodontics, every extraction is a strategic decision—one that could determine the future of a patient’s perfect smile!

(And if all else fails, there’s always the stainless steel crown—a knight in shining armor for struggling FPMs everywhere!)