Headgear & RME: A Dynamic Duo or Just Extra Work? 🤔

Class II malocclusion—aka the “overbite situation”—is like a dental tug-of-war between the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandible (lower jaw). Sometimes, the upper jaw is a little too enthusiastic and needs to be held back while the lower jaw plays catch-up. Enter headgear, the OG of growth modification since the 1950s! 🎩🦷

Why Headgear?

Think of it as a seatbelt for your upper jaw—it stops excessive forward movement while letting the lower jaw grow at its own pace. 🚗💨 Studies show headgear can reduce facial convexity (goodbye, profile selfies with extra chin tucks!) and improve the sagittal relationship between the upper and lower dental arches. 📏✨

But What About a Narrow Upper Jaw?

Class II cases often come with maxillary constriction, meaning the upper arch is too narrow—like trying to fit a king-size blanket on a twin bed. 🛏️ Solution? Rapid Maxillary Expansion (RME)! 💥 By widening the upper arch, RME makes more space for the teeth and helps balance the bite.

The Real Question: RME + Headgear = Worth It?

Some say expanding the maxilla first helps headgear work even better. Others wonder, “Why add more hardware when headgear alone does the job?” 🤷♂️ That’s exactly what this study aims to find out—comparing maxillary skeletal and dental effects when using combined headgear alone vs. headgear + RME.

👨⚕️ The Study Setup: Who, What, Where?

🔬 Study Type: Experimental (aka, “let’s test this on real people!”)

📍 Location: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 🇧🇷

👦👧 Participants: 41 kids with Class II, Div 1 malocclusion + 20 Class I controls

🦷 Treatment: Combined Headgear (CH) alone vs. RME + CH

📏 Assessment Tool: Lateral cephalograms 📸

📊 How Were They Grouped?

| Group | Who’s In? | What’s Happening? |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (CH) | 20 Class II kids (8 boys, 12 girls) | Wore combined headgear 12-14 hrs/day for 6 months 🕒 |

| Group 2 (RME+CH) | 21 Class II kids (10 boys, 11 girls) | First did RME for 14 days, then combined headgear for 6 months🔧🦷 |

| Group 3 (Control) | 20 Class I kids (8 boys, 12 girls) | Just space supervision, no fancy gadgets 🚫 |

📏 Baseline Skeletal Stats (T1): Were They Even Comparable?

| Measurement | Group 1 (CH) | Group 2 (RME+CH) | Group 3 (Control) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandibular Plane Angle (SN.GoGn) | 36.9° ± 3.9° | 36.4° ± 6.3° | 36.9° ± 4.1° |

| ANB Angle (Class II if > 4°) | 5° ± 1.9° | 5.9° ± 1.8° | 3.7° ± 2.2° |

✔️ All groups had similar skeletal patterns (slightly hyperdivergent).

✔️ Class II groups (CH & RME+CH) had significantly higher ANB than controls (duh!).

⚙️ Treatment Protocols: How Did They Torture—Err, Treat—The Kids?

🦷 Group 1 (CH Only):

✅ Headgear worn 12-14 hours/day for 6 months

✅ Inner bow expanded 2mm before insertion into molar tubes

✅ Force applied: 300g/f per side in cervical + parietal directions

✅ Resultant force vector: 424g/f

🦷 Group 2 (RME + CH):

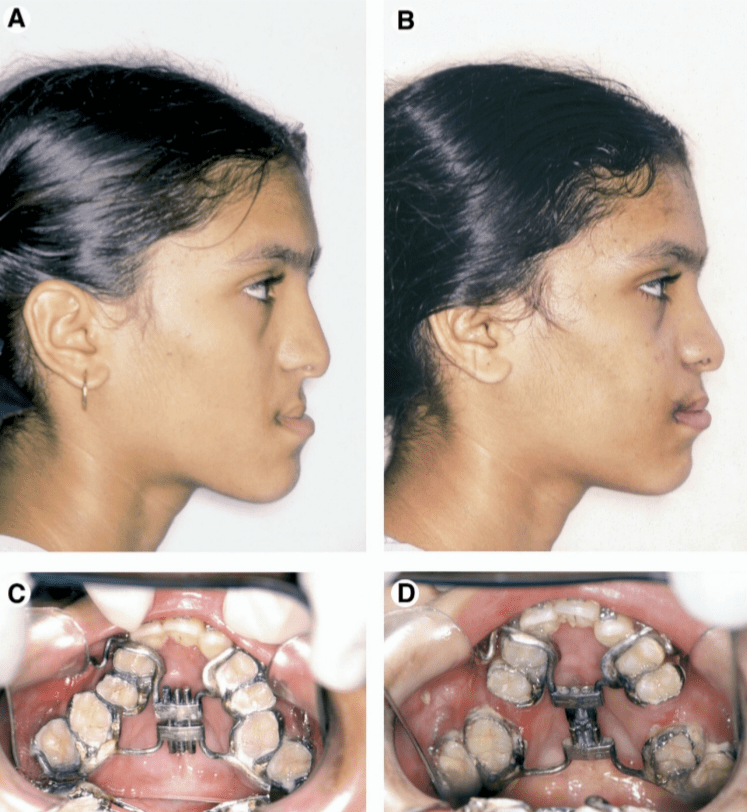

🔧 Step 1: RME Phase (14 days)

- Modified Haas Expander (banded from 1st molars → premolars/deciduous molars)

- Activated 4x on day 1, then 2x/day until transverse overcorrection achieved 💥

🦷 Step 2: CH Therapy (6 months)

- Same headgear protocol as Group 1 (CH), just started 7 days into expansion

📸 Follow-Up (T2): What Happened Next?

📅 Timeline:

- Experimental groups (CH & RME+CH): Cephs taken once Class I molar relationship achieved (~6 months)

- Control group: Cephs taken 6 months later (nothing changed, just grew normally)

👀 Cephalometric Analysis:

- Blinded operator digitized landmarks using Dentofacial Planner Plus (DFP 2.0)

- Statistical Analysis:

- Student’s t-test for before-after comparisons

- ANOVA & Tukey’s tests for inter-group differences

Headgear vs. RME + Headgear: Who Wins the Class II Battle? 🦷⚔️

So, what really happened after 6 months of headgear and expansion drama? Did we just push teeth back, or did we actually fix something?

🔬 The Molar Drama: Distalization, Tipping & More!

When you strap a headgear on a patient, you expect those maxillary molars to back off a little, right? Well, they did! But let’s get into the juicy details.

| Molar Effects 🦷 | Group 1 (CH Only) | Group 2 (RME + CH) | Significance 📌 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maxillary molars moved distally | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Both groups had distal movement! |

| Maxillary molars tipped distally | ✅ Yes (6.4°) | ❌ No tipping (1.4°) | Tipping only in CH group! |

| Difference in tipping between groups? | ❌ No significant difference | ❌ No significant difference | Tipping happened, but RME didn’t change the game! |

| Maxillary molar extrusion? | ❌ Nope | ❌ Nope | No molars were harmed in the making of this study! 😂 |

🎯 Key Takeaway:

- Headgear alone (CH) made maxillary molars tip backward.

- Adding RME (CH + RME) prevented tipping, but the amount of distal movement was the same in both groups.

- Neither group showed molar extrusion. So, no unwanted gummy smiles! 😃

🏠 What Happened to the Maxilla?

Did we actually hold that maxilla back, or did we just give the patient extra metal to wear?

| Maxillary Effects 🏠 | Group 1 (CH Only) | Group 2 (RME + CH) | Significance 📌 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clockwise maxillary rotation? | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | Only CH group showed rotation! |

| Forward maxillary growth restriction? | ❌ No | ✅ Yes | RME + CH held maxilla back better! |

| Difference in maxillary changes between groups? | ❌ No significant difference | ❌ No significant difference | Effects were subtle between groups. |

📌 Clockwise rotation of the maxilla was seen in Group 1 (Cervical Headgear Alone) but was not significantly different from Group 2 (Cervical Headgear + RME).

🧐 Why does this matter?

- Molars act as anchors for headgear forces. If the force is applied at a lower level, the maxilla tilts clockwise⏩🔄.

- This tilts the occlusal plane and can make deep bite & excessive gingival exposure worse! 😱

Ortho Wisdom of the Day:

❌ Class II + Deep Bite + Excess Gingival Display = BAD combo for cervical headgear alone!

✅ Use high-pull headgear instead—its force vector passes through or above the maxilla’s center of resistance, preventing excessive rotation. 💡

🎯 Key Takeaway:

- Headgear alone (CH) rotated the maxilla clockwise a bit.

- RME + CH restricted forward growth of the maxilla.

- No major differences between groups—so, was RME really necessary? 🤔

⏳ How Long Did It Take to Achieve Class I?

Let’s face it, patients hate long treatments. So, which group got to a Class I molar relationship faster?

| Group | Time to Class I Molar Relationship |

|---|---|

| CH Only (Group 1) | ⏳ 6.5 ± 1 months |

| RME + CH (Group 2) | ⏳ 5.5 ± 1.1 months |

🎉 Winner: RME + CH shaved off 1 month! But was it worth the extra hassle? 🤷♂️

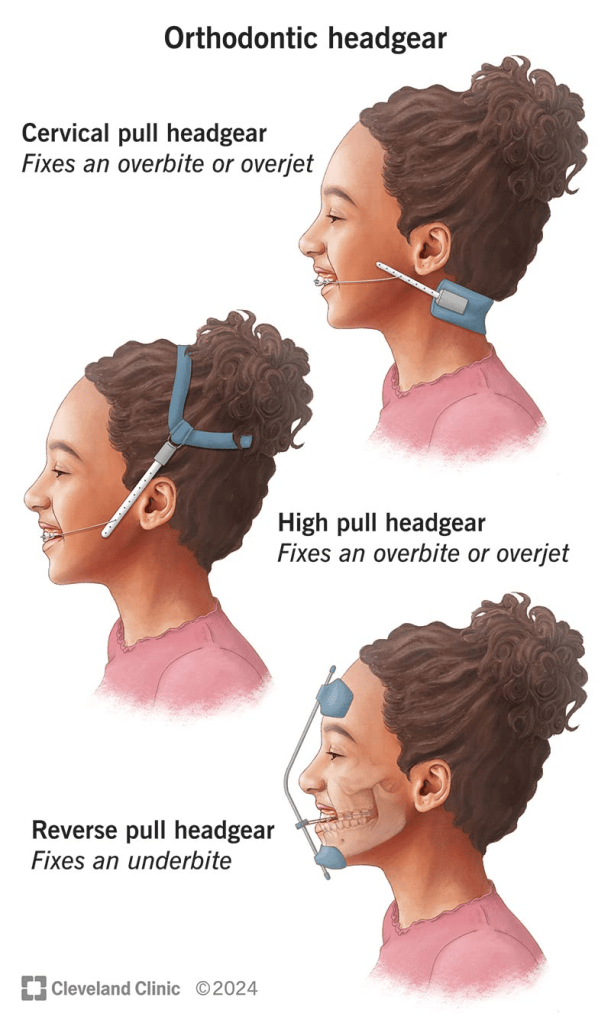

🦷 Why Headgear? And Which One?!

If you’ve ever had a patient ask, “Why do I have to wear this medieval torture device?”—here’s your answer:

| Type of Headgear 🎭 | Best For… 👩⚕️ | Why? 🤓 |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical Headgear (CH) | Hypodivergent or mesodivergent faces | Allows some molar extrusion, doesn’t mess with facial esthetics. ✅ |

| High-Pull Headgear | Hyperdivergent faces, open bites | Keeps molars in check, prevents jaw from tipping backward. 🚫 |

| Combined Headgear (CH + High-Pull Forces) | Mesodivergent & hyperdivergent faces | Controls molar movement while keeping things balanced. ⚖️ |

🎯 Key Takeaway:

- Cervical headgear? Great for low-angle cases, but it can increase vertical growth. 😬

- High-pull headgear? Best for high-angle cases to prevent open bite.

- Combined headgear (CH)? The middle ground—good for most Class II, especially hyperdivergent cases!

So, if your Class II patient is growing like a giraffe 🦒, go for combined or high-pull headgear. Otherwise, cervical may do the trick!

🦷 The Science Behind Headgear Design

The way a headgear is designed determines its effects. Let’s take a look at what happens when we tweak the outer bow:

| Headgear Bow Design 🎭 | Effect on Molars 🦷 | Impact on Mandible 👀 |

|---|---|---|

| Longer & Downward Angled | More vertical force, avoids extrusion, but increases distal tipping 📉 | Can help in hyperdivergent cases! ✅ |

| Shorter Outer Bow (Cervical Headgear) | More horizontal force, prevents excessive molar tipping | Keeps mandible stable 📏 |

| Upward Angled Bow 🚀 | Eliminates tipping, but causes extrusion! 😱 | Leads to clockwise mandibular rotation(bad for Class II) 🚨 |

🎯 The Takeaway:

- If you don’t want molars tipping too much, keep the bow shorter!

- If you’re worried about extrusion messing up the occlusion, avoid upward-angled bows!

🦷 What About Transverse Maxillary Deficiency?

Class II Division 1 isn’t just about protruded upper teeth—there’s often a hidden transverse problem! 😲

| Issue 🤯 | How It Affects Class II? 📉 | Solution? ✅ |

|---|---|---|

| Narrow maxillary arch | Makes the mandible sit back | RME to unlock forward mandibular growth! 🏗️ |

| Constricted canine region | Pushes the lower jaw backward | Widen it to allow natural AP growth! 📈 |

🎯 Key Takeaway:

- If the maxilla is too narrow, mandibular growth gets blocked—making Class II even worse!

- RME before headgear? Yes! Expanding first means the mandible can move forward naturally.

So, if your Class II patient has a narrow upper arch, don’t just throw headgear at them—widen it first! 🚀

🤓 Headgear vs. Headgear + RME – Which is Better

| Feature 🔬 | CH Alone | CH + RME |

|---|---|---|

| Distal molar movement 🚀 | ✅ Good | ✅ Good |

| Distal tipping 🤷♂️ | 6.4° (More) 📉 | 1.4° (Less) ✅ |

| Molar extrusion 📏 | ❌ None | ❌ None |

| Clockwise maxillary rotation 🔄 | ✅ Happened | ❌ Prevented |

| Restriction of forward maxillary growth ⏳ | ❌ No significant restriction | ✅ More restriction 📉 |

🦷 The Final Takeaway: What Should YOU Do?

🔹 If your Class II patient has a narrow maxilla, use RME before headgear—it’s a game-changer! 🎮

🔹 High-pull headgear might be a better choice if you want to avoid maxillary rotation. 🏗️

🔹 No single approach is perfect—your treatment should be customized based on facial pattern & occlusion.

📜 Conclusion: The Ortho Cheat Sheet 📜

✅ Distal movement of maxillary molars happens with both CH & CH+RME.

❌ Distal tipping occurs ONLY with CH alone.

❌ Clockwise rotation of the maxilla happens more with CH alone.

⚡ RME before headgear speeds up treatment & minimizes unwanted side effects!