Angle’s Class I malocclusion is one of the most common types of dental misalignment encountered in clinical practice. It refers to a situation where the upper and lower teeth are generally aligned, but various issues such as crowding, spacing, bidental protrusion, vertical problems (deep bite or open bite), and transverse issues (crossbite or scissor bite) can arise. The good news is that these issues are typically easier to treat compared to more complex malocclusions, giving patients a higher chance of successful outcomes.

The Role of Growth in Achieving Class I Malocclusion

It’s important to understand that many of us begin with a skeletal Class II pattern during early development. With favorable growth, the individual’s skeletal structure may gradually transition into a skeletal Class I relationship. For example, a patient presenting with a mild facial convexity in mixed dentition can often be expected to develop a straighter profile as they continue to grow. This process occurs as growth in all three spatial planes—vertical, transverse, and sagittal—happens synchronously, ultimately resulting in a Class I skeletal configuration.

As this growth progresses, the facial profile becomes less convex, giving the appearance of a more balanced, harmonious face. Therefore, many orthodontic cases that are deemed successful are a combination of favorable natural growth and orthodontic intervention.

Focus on Intraarch Alignment and Interarch Occlusion

In patients with Angle’s Class I malocclusion, the anteroposterior skeletal relationship is normal. The primary goal of orthodontic treatment in these cases is to focus on correcting intraarch alignment and interarch occlusal relations. Treatment options vary depending on the individual case and may include:

- Extractions: Often used to create space when necessary.

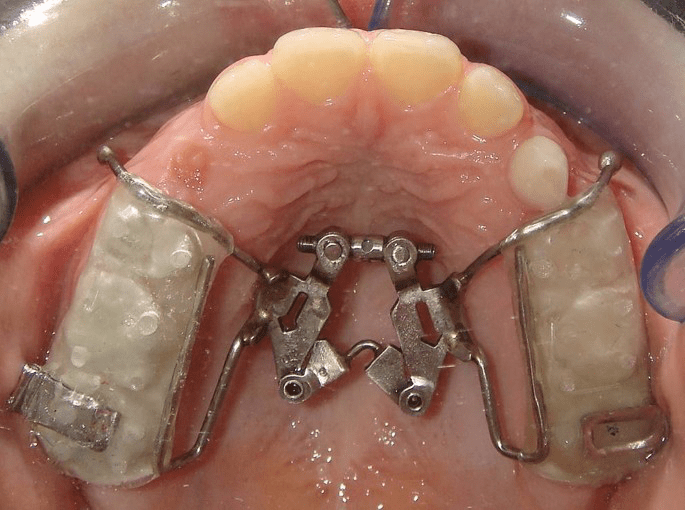

- Non-extraction approaches: These can include slenderization (reducing the size of teeth), expansion (widening the dental arch), distalization (moving the back teeth backwards), derotation (correcting the rotation of posterior teeth), and proclination (moving retroclined anterior teeth forward).

Managing Specific Class I Malocclusion Issues

Crowding and Spacing: Spacing issues in the dental arch can occur for various reasons, such as hypodontia (missing teeth) or microdontia (abnormally small teeth). Hypodontia often affects the maxillary lateral incisors and mandibular premolars. In these cases, the orthodontist must decide whether to open space for prosthetic replacements or to close the space orthodontically. On the other hand, microdontia can be managed through space redistribution and the aesthetic build-up of smaller teeth.

Bidental Protrusion: Bidental protrusion is another common concern seen in patients with a Class I skeletal base. This condition can often be efficiently managed with premolar extractions, which help reduce the protrusion and bring the teeth into better alignment.

Vertical and Transverse Problems: While Class I malocclusion is generally associated with a normal anteroposterior skeletal relationship, vertical (deep bite or open bite) and transverse issues (crossbite or scissor bite) may still be present. These concerns are often addressed in subsequent stages of orthodontic treatment.

Conclusion

Angle’s Class I malocclusion is a frequent and treatable condition seen in orthodontic practice. The successful outcomes often stem from a combination of natural growth and targeted orthodontic interventions. Whether addressing crowding, spacing, bidental protrusion, or vertical and transverse problems, orthodontists can employ various techniques such as extractions, slenderization, expansion, and more to achieve optimal results. Understanding the underlying growth patterns and employing the right treatment plan is key to ensuring that patients achieve a balanced, functional, and aesthetically pleasing smile.