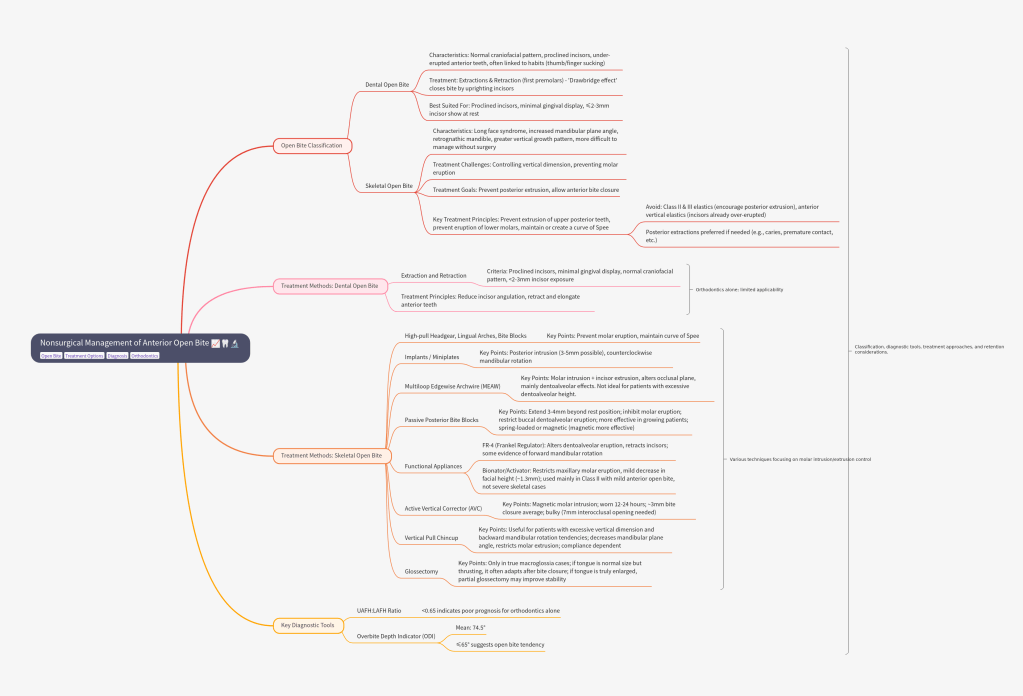

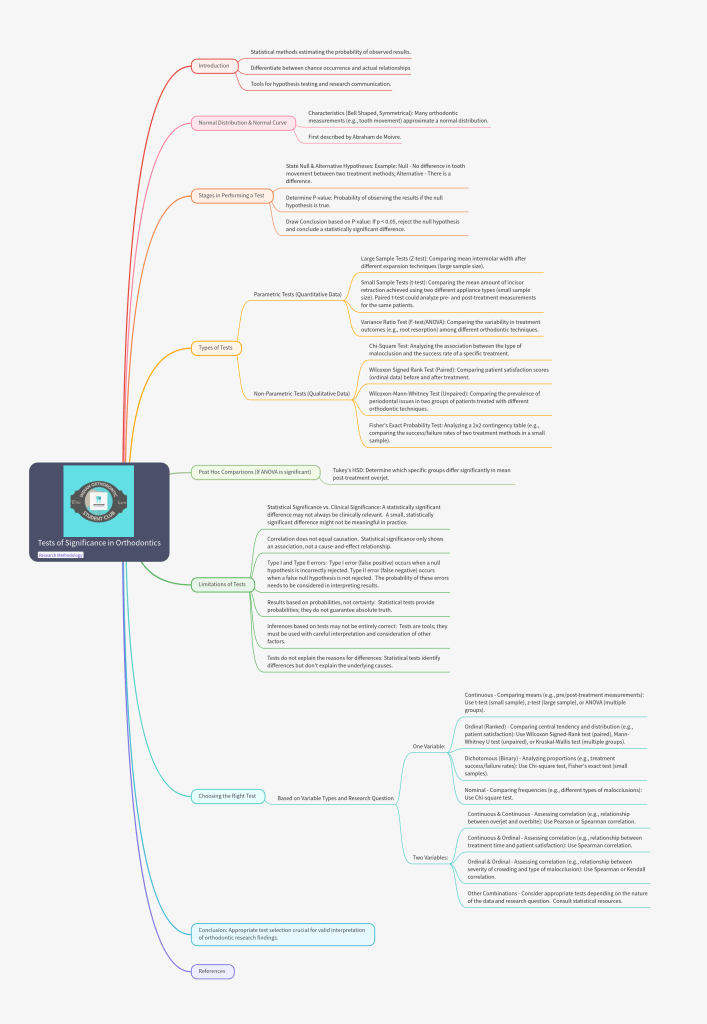

Anterior open bite has always been one of the most challenging malocclusions to treat. Patients often present with esthetic concerns, speech difficulties, and compromised function. While orthognathic surgery is a definitive option for severe skeletal open bites, not all patients are candidates—or willing—for surgery. Fortunately, nonsurgical strategies can offer promising results when case selection is appropriate.

🔍 Understanding the Problem

Open bite malocclusion can be dental or skeletal in origin:

- Dental open bite:

▸ Normal craniofacial pattern

▸ Proclined incisors, under-erupted anterior teeth

▸ Often linked to habits like thumb/finger sucking - Skeletal open bite:

▸ Long face syndrome, ↑ mandibular plane angle, retrognathic mandible

▸ Greater vertical growth pattern

▸ More difficult to manage without surgery

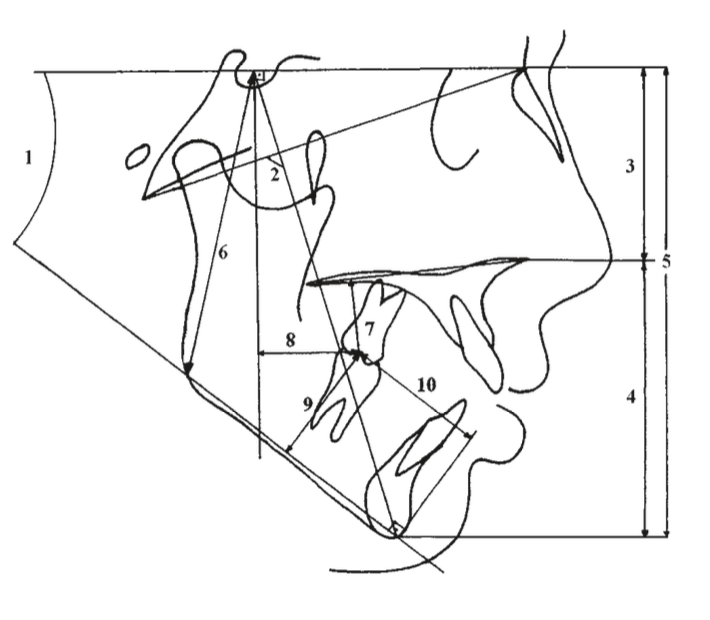

Key Diagnostic Tools

- UAFH : LAFH ratio (<0.65 → poor prognosis for orthodontics)

- Overbite Depth Indicator (ODI)

▸ Mean: 74.5°

▸ ≤65° → open bite tendency

Treatment Approaches

A. Dental Open Bite

- Extractions & retraction (first premolars) → “drawbridge effect” closes the bite by uprighting incisors.

- Best suited for patients with:

✅ Proclined incisors

✅ Minimal gingival display

✅ ≤2–3 mm incisor show at rest

B. Skeletal Open Bite (Nonsurgical Options)

Skeletal open bite is much harder to correct nonsurgically than dental open bite. The central challenge lies in controlling vertical dimension—particularly by preventing or reducing molar eruption.

Goals: prevent posterior extrusion, allow anterior bite closure.

⚖️ Key Treatment Principles

- Prevent extrusion of upper posterior teeth

- Prevent eruption of lower molars

- Maintain or create a curve of Spee

- ❌ Avoid Class II & III elastics (encourage posterior extrusion)

- ❌ Avoid anterior vertical elastics (incisors already over-erupted)

- Posterior extractions preferred if needed (e.g., caries, premature contact, etc.)

👉 Clinical insight: For every 1 mm molar intrusion, you can achieve about 3 mm anterior bite closure through mandibular counterclockwise rotation.

| Method | Key Points |

|---|---|

| High-pull headgear, lingual arches, bite blocks | Prevent molar eruption; maintain curve of Spee. |

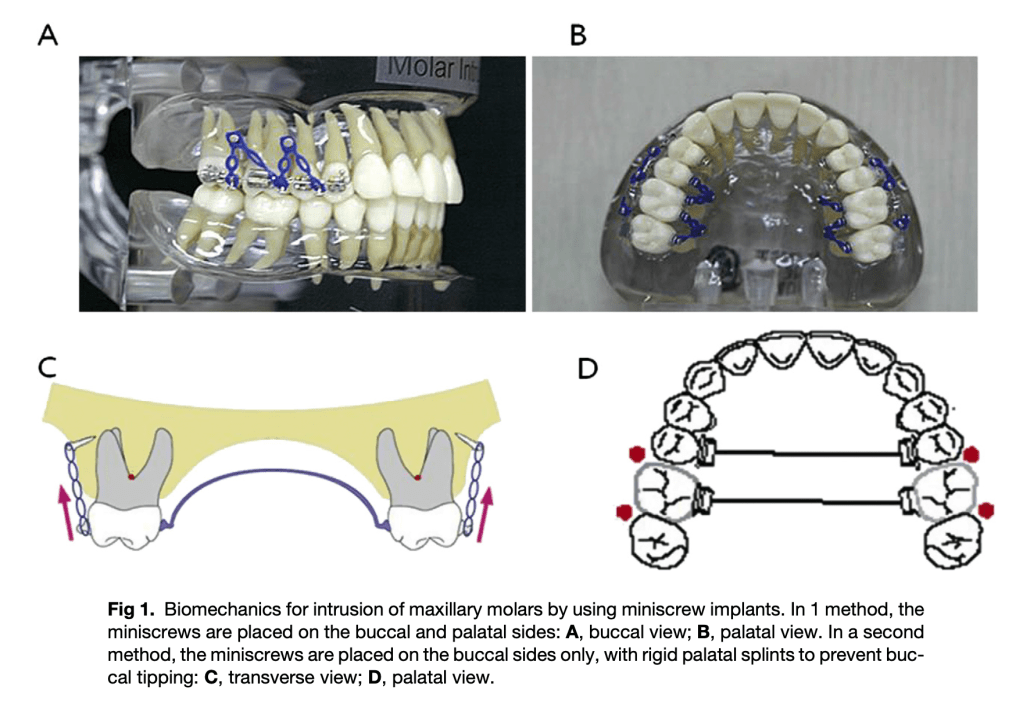

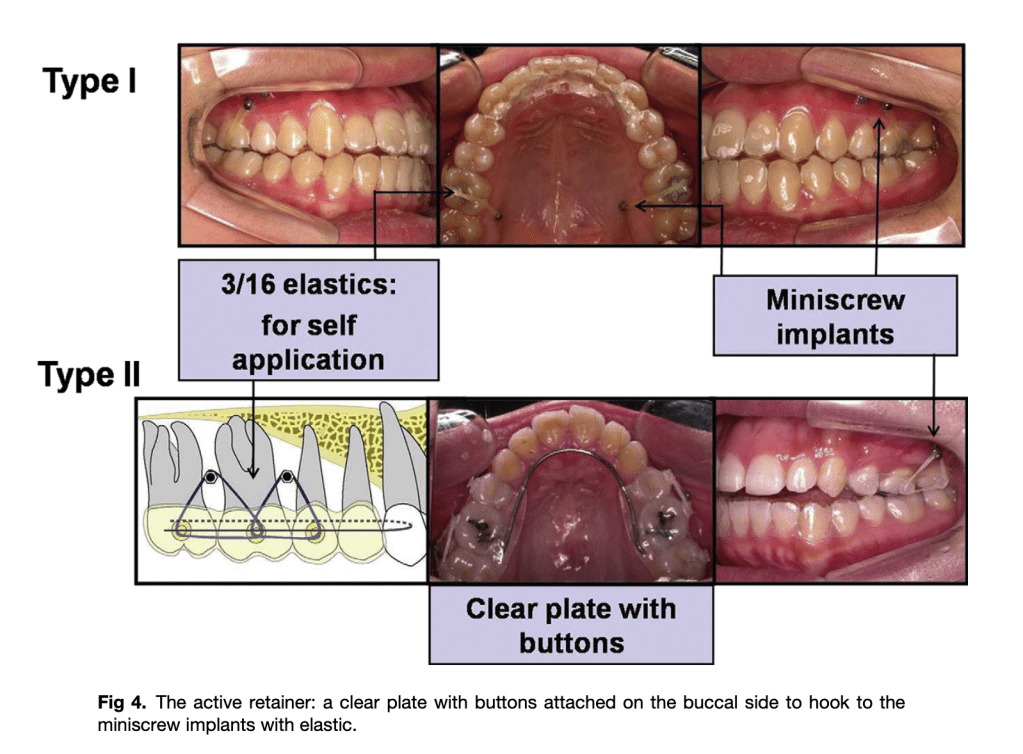

| Implants / Miniplates | Posterior intrusion (3–5 mm possible); counterclockwise mandibular rotation. |

| Multiloop Edgewise Archwire (MEAW) Multilooped .016 × .022 SS wires + heavy anterior elastics | Molar intrusion + incisor extrusion; alters occlusal plane; mainly dentoalveolar effects. Not ideal in patients with already excessive dentoalveolar height. |

| Passive Posterior Biteblocks extend 3–4 mm beyond rest position | Inhibit molar eruption; Restrict buccal dentoalveolar eruption → allow mandibular autorotation forward, hence more effective in growing patients; can be spring-loaded or magnetic (more effective; ~3 mm improvement vs 1.3 mm for spring type) |

| Functional Appliances – Open bite is worsened by faulty orofacial muscle posture. | FR-4 (Frankel regulator): Alters dentoalveolar eruption, retracts incisors. Some evidence of forward mandibular rotation. Bionator/Activator: Restricts maxillary molar eruption, mild decrease in facial height (~1.3 mm). Used mainly in Class II with mild anterior open bite, not severe skeletal cases. |

| Active Vertical Corrector (AVC) – using samarium cobalt magnets embedded in acrylic. | Magnetic molar intrusion; worn 12–24 hrs; ~3 mm bite closure avg, bulky (7 mm interocclusal opening needed) |

| Vertical Pull Chincup | Useful for patients with excessive vertical dimension and backward mandibular rotation tendencies. ↓ mandibular plane angle, restricts molar extrusion; compliance dependent. |

| Glossectomy | Only in true macroglossia cases. If tongue is normal in size but thrusting, it often adapts after bite closure → surgery not needed. If tongue is truly enlarged relative to oral cavity → partial glossectomy may improve stability. |

🔄 The Retention Challenge

One of the biggest hurdles in open bite management is long-term stability.

Studies show relapse rates of 35–43%.

Relapse is often due to dentoalveolar rebound rather than skeletal relapse.

Retention strategies:

Long-term/fixed retainers

Retainers with occlusal coverage to limit molar eruption

Tongue crib when tongue posture is contributory

DOWNLOAD THE PAPER HERE:

SPOTIFY EPISODE LINK: https://creators.spotify.com/pod/profile/dr-anisha-valli/episodes/Nonsurgical-Management-of-Anterior-Open-Bite-e376eng