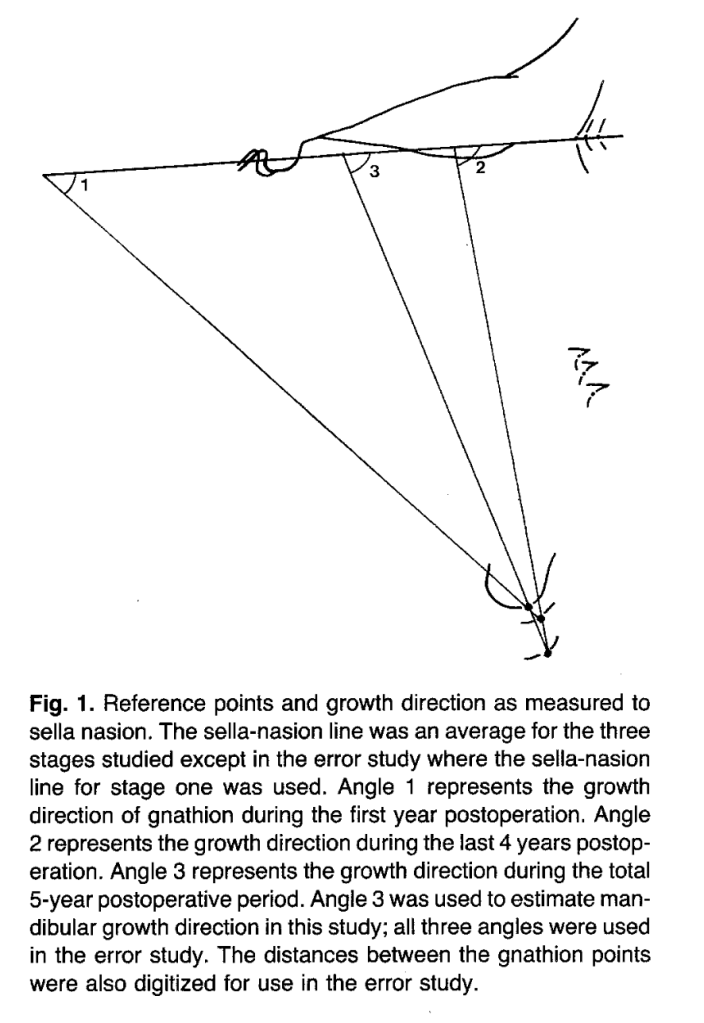

1. Why is the inter-incisor angle critical to stability in Class II div 2?

- Class II div 2 has increased inter-incisor angle

- Excessive angle → deep overbite and mandibular locking

- Normalizing angle:

- Reduces vertical overlap

- Allows lower incisors to sit in zone of balance

- Palatal torque of upper incisors is essential

- If angle is not corrected → lower incisors relapse

Viva punchline:

👉 Stable overbite correction depends on normalization of the inter-incisor angle.

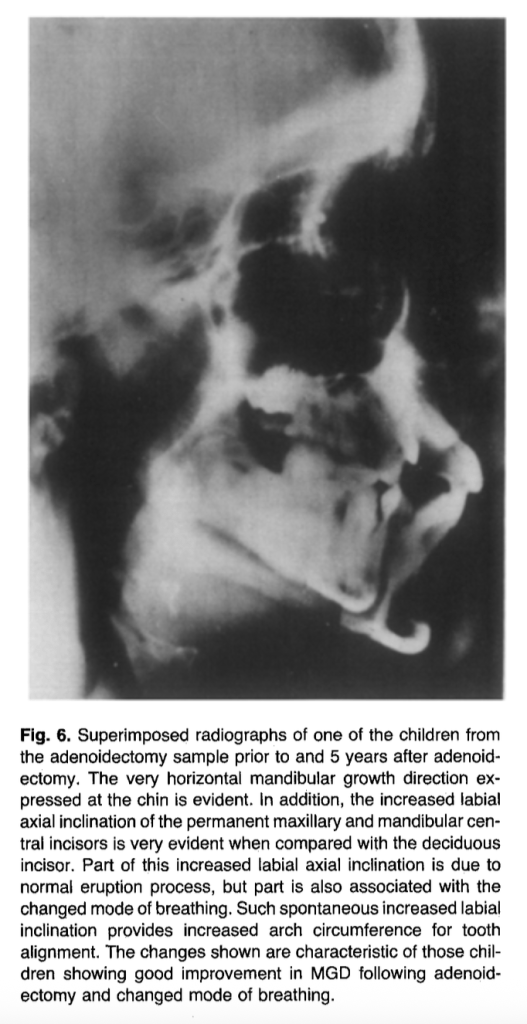

2. Why doesn’t lower incisor advancement relapse?

- Relapse occurs only if teeth move outside muscular envelope

- Lower incisors are advanced:

- Within lower lip contour

- Not beyond soft-tissue limits

- Simultaneous:

- Upper incisor intrusion

- Palatal torque

- This unlocks the mandible

- New incisor position becomes physiologic

Viva punchline:

👉 Because the lower incisor is advanced within the soft-tissue envelope.

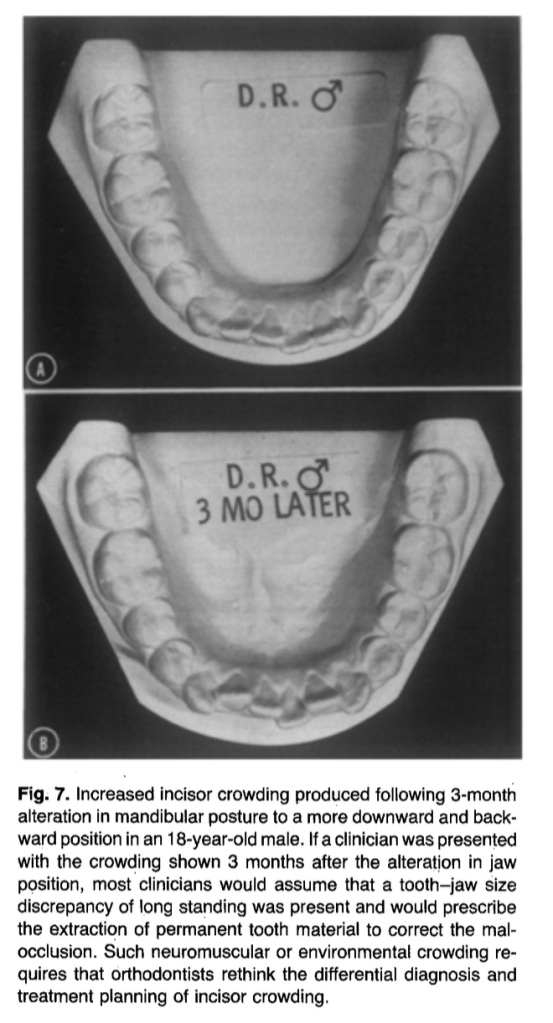

3. Why is flattening the curve of Spee essential?

- Class II div 2 → exaggerated curve of Spee

- Lower incisor advancement creates:

- ~4–5 mm space anteriorly

- ~8–10 mm total

- ~2 mm per side used for:

- Flattening curve of Spee

- Remaining space used for alignment

- Flattening is part of correction, not space loss

Viva punchline:

👉 Curve of Spee flattening enables non-extraction treatment.

4. Why upper removable appliance first?

- Achieves multiple goals simultaneously:

- Bite opening

- Upper incisor palatal torque

- Buccal segment distalization

- Correction of scissor bite

- Upper incisor intrusion

- Frees mandible from locked position

- Fixed appliance alone cannot do this efficiently

Viva punchline:

👉 Upper removable appliance provides coordinated first-phase correction.

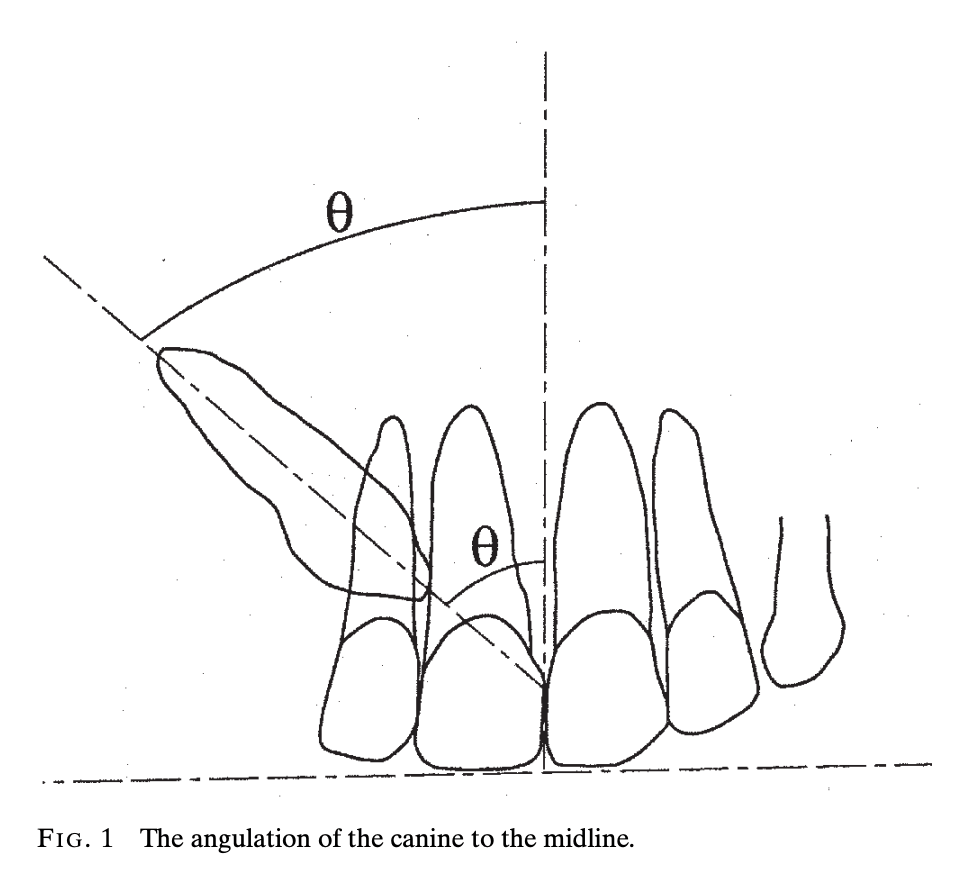

5. Importance of upper incisor centroid

- Centroid = midpoint of incisor root

- Helps assess:

- Root position

- Torque control

- Lower incisor tip position relative to centroid determines:

- Inter-incisor angle

- Stability

- Lower incisor behind centroid → unstable

- Slightly ahead → stable relationship

Viva punchline:

👉 Centroid guides stable inter-incisor positioning.

6. When to extract? Why not first premolars?

- Extractions only if:

- Severe skeletal discrepancy

- Inadequate space after leveling

- First premolar extraction:

- Compromises buccal segment correction

- Second premolars preferred:

- Maintain Class I molar correction

- Decision after therapeutic diagnosis

Viva punchline:

👉 Extraction decisions are delayed and conservative in Class II div 2.

7. Why long-term lower bonded retainer?

- Lower anterior relapse is unpredictable

- Tight perioral musculature common

- Lower anterior segment is foundation of correction

- Bonded retainer:

- Maintains AP and transverse position

- Stable lower incisors support upper incisors

- Upper arch often needs minimal retention

Viva punchline:

👉 Lower bonded retainer ensures long-term stability.

8. Role of upper incisor–lip relationship

- Upper incisor should:

- Contact inner slope of lower lip

- Show 2–3 mm at rest

- Defines soft-tissue boundary

- Dictates:

- Amount of intrusion

- Palatal torque

- Aesthetic goal = biomechanical goal

Viva punchline:

👉 Soft-tissue aesthetics guide incisor positioning.

9. Why no encroachment on lower lip?

- Teeth outside soft-tissue envelope relapse

- Lower lip exerts strong muscular pressure

- Advancing beyond lip contour → instability

- Staying within lip contour ensures:

- Muscular support

- Long-term stability

Viva punchline:

👉 Respecting the soft-tissue envelope prevents relapse.

10. Therapeutic diagnosis and extraction decision

- Therapeutic diagnosis = diagnosis through treatment response

- In Class II div 2:

- Complete first-phase correction

- Reassess space and alignment

- Avoid premature extraction decisions

- Especially useful in borderline cases

Viva punchline:

👉 Extraction is decided after observing treatment response.