The interior of a tooth, the endodontium, is to a large extent hidden from direct inspection by the operator. Even passing roentogen rays through the tooth provides only limited clues to the structure. For this reason, much time and energy have been invested in research into the “normal” anatomy and the statistical incidence of different variations in form (review: Bauman 1995). It is hoped that this information will be helpful in the daily practice of endodontics. This research has already created awareness of the complexity of the root canal system, which is not simply conical tube but rather a branching system with a pulp chamber, primary canals, lateral canals (communicating with the periodontium), and accessory canals (multiple ramifications in the apical third of the root). This knowledge is a basic requirement for successful endodontic treatment. The theoretical pulpal anatomy that we expect to encounter, though, can only provide initial orientation because the actual situation encountered during treatment always reveals new variations.

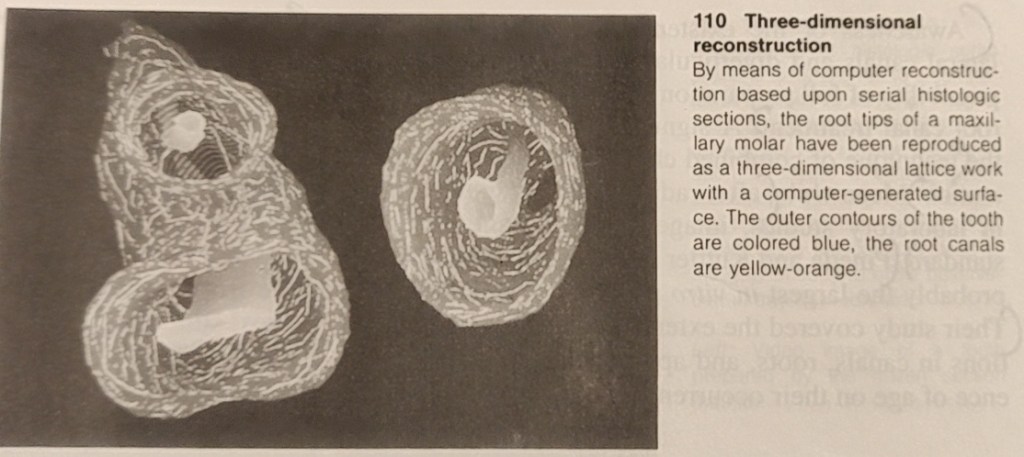

The first detailed systematic description of root canal anatomy found in the literature is by Carabelli (1844). The same manner of representation with longitudinal and transverse sections in different planes is still used in modern textbooks (eg., Cohen and Burns 1994). Some of these illustrations go back to the original sections and serial sections (Black 1902; Miller 1904). In addition to direct observation with the unaided eye and the microscope, the chemical dissolution method has provided much valuable information. In this process the tooth is opened, the pulp digested, and the empty pulp space filled. The famous Swiss pulp researcher Hess (1917) perfected this technique in which he filled the pulp space with vulcanized India rubber and then dissolved the surrounding tooth substance with 50% hydrochloric acid. This acid dissolution preparation showed the complex branching of the pulp tissues and, with it, the root canal system. Whereas the previous sections, slides, and drawings were only two-dimensional, now for the first time it was possible to see a spatial representation of the entire root canal system. Hess studied 2800 teeth of the permanent human dentition and his student Zurcher (1922) studied deciduous teeth. Together they gathered statistical data on the number of canals and their ramifications.

METHODS OF REPRODUCING ROOT CANAL ANATOMY

Most techniques require the destruction of the tooth. However, at the beginning of the twentieth century the transparency method was developed (Adolf 1913) in which the integrity of the tooth and the spatial relationships of the root canal and its outer contours were preserved. Various substances (from colored gelatin and paraffin to silicone) were introduced into the pulp space through an access opening, and the tooth was then made transparent by means of oil of cedar, benzol, salicylic acid compounds.

While histologic sections have long provided information on the structure of the root canal and the pulp tissue, Meyer (1955-1970) set new standards. From special sections of all 16 types of permannet teeth he made 50x scale models of the apical canals (the last 6 mm of each) of 800 teeth by projecting the circumference of the canals and building wax models layer by layer. This study further clarified the complexity of the pulp space, from then on called the root canal system (Meyer 1955 b, 1960).

Awareness of the existence of large numbers of lateral canals and diverticula renders obvious the impossibility of full preparation of all the branches during root canal treatment. Asignificant outcome of this is the technique of combined chemical-mechanical preparation. After radiographs began to be used in laboratory studies, images in two planes became standard. Pineda and Kutler (1972) performed what is probably the largest in vitro study on over 40000 teeth. Their study covered the extent of branching and variations in canals, roots, and apical deltas, and the influence of age on their occurence.

Hession (1977a-d) showed the shape of the root canal system radiographically before and after in vitro treatment. The abundant range of research tools is complemented by in vivo radiographs, microradiographs, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), computer reconstructions, monographs of individual cases, and many other aids (Baumann 1995). Subsequently, an immense body of facts has been accumulated and these are presented in excellent didactic style in books,videos, slide series, reports, seminars, and demonstration. This new information should be offered in further education courses (Baumann 1994, 1955).

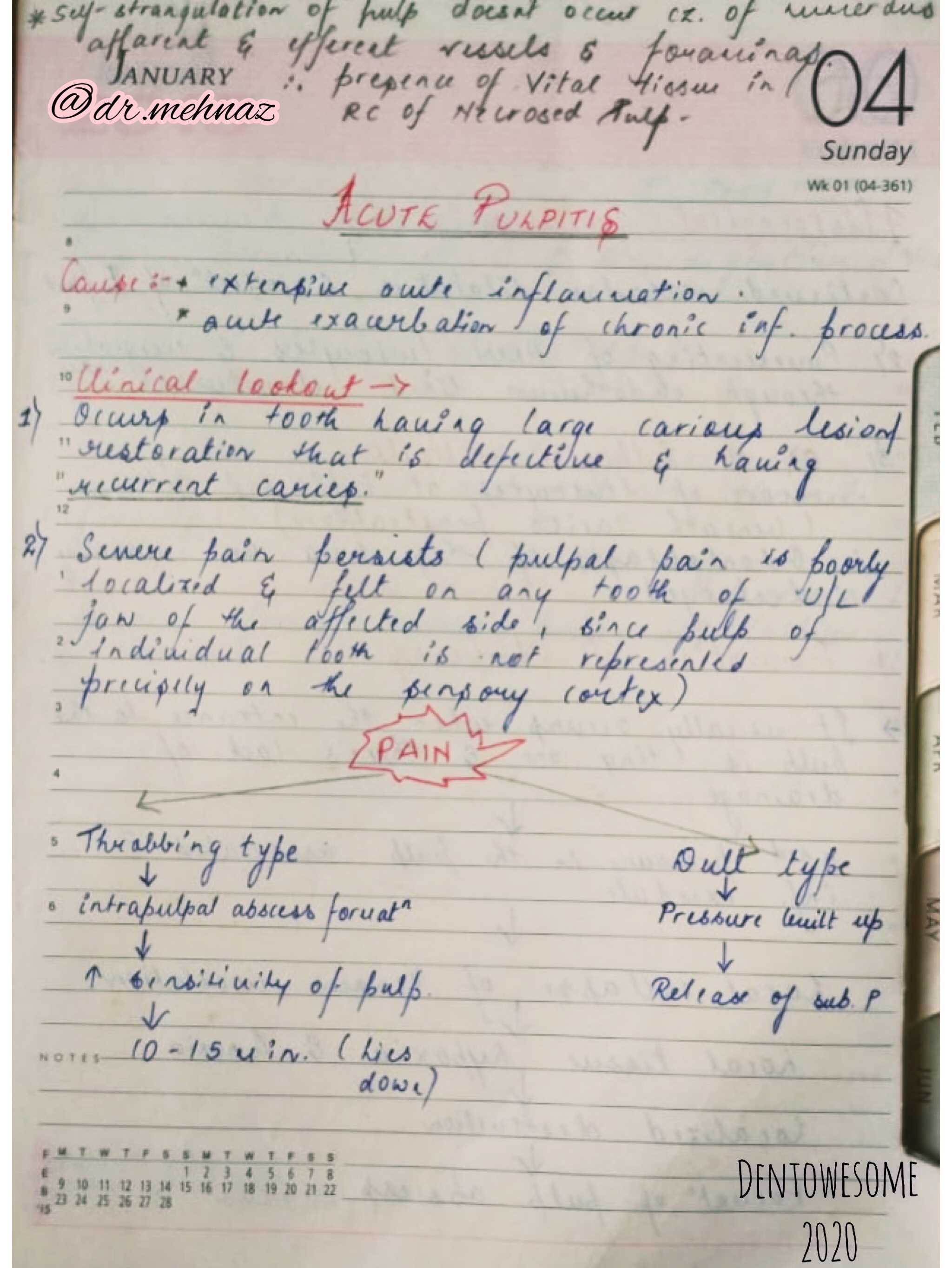

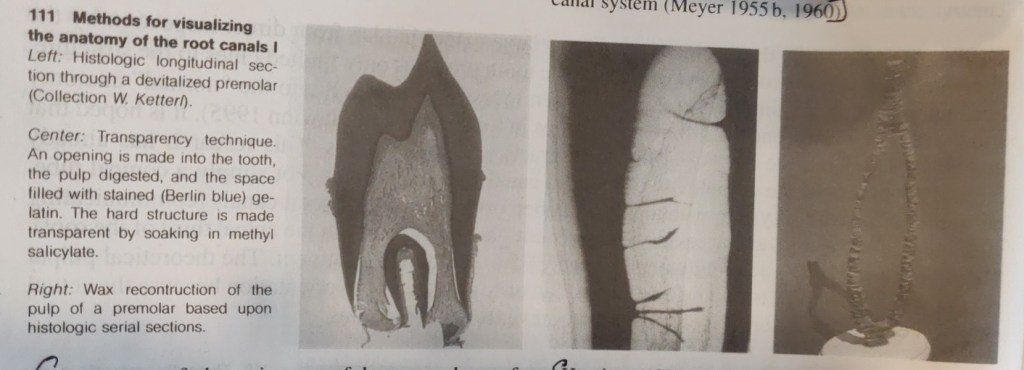

THREE – DIMENSIONAL COMPUTER RECONSTRUCTION

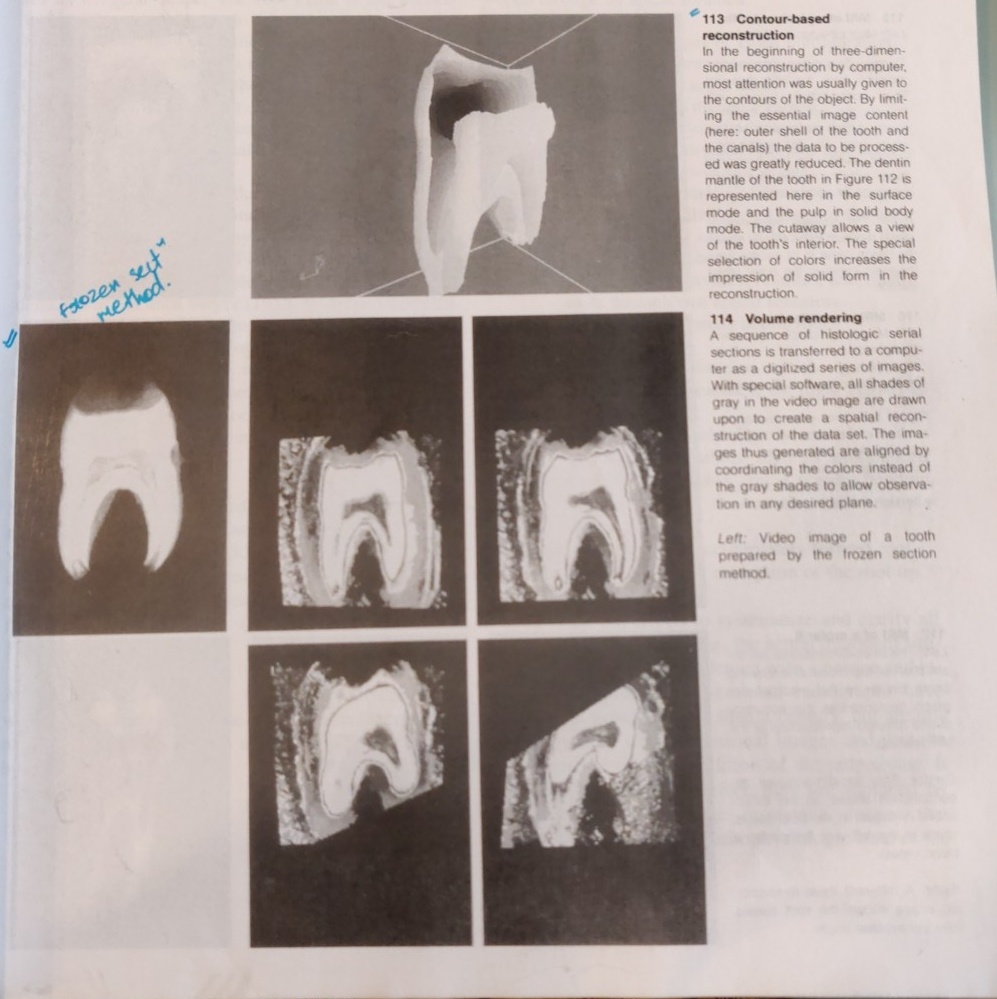

From a historical perspective we see a long tradition of striving to better describe the anatomy of the teeth. Preparations of 20 micrometer thick frozen sections were continuously recorded on videotape, producing data to serve as the basis for computerized three-dimensional reconstructions. In a contour-based reconstruction only the surface outlines of the tooth and the canals are used for input (Baumann et al. 1993d, 1994b). From this emerges a contour line, surface, or solid body model that can be viewed from any desired angle.

Faster computers permit the use of all shades of gray in a video image to create a volume-based reconstruction (volume rendering). Through ray-tracing, isotropic voxels (points in space) are created in which the raw unaltered data is drawn upon for three-dimensional reconstruction (Baumann 195, Baumann et al. 1993d).

Images are created that can be viewed, sectioned, colored, zoomed, or rotated in any desired plane. This makes possible views into the endodontic space that were prevoiusly unknown.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING (MRI)

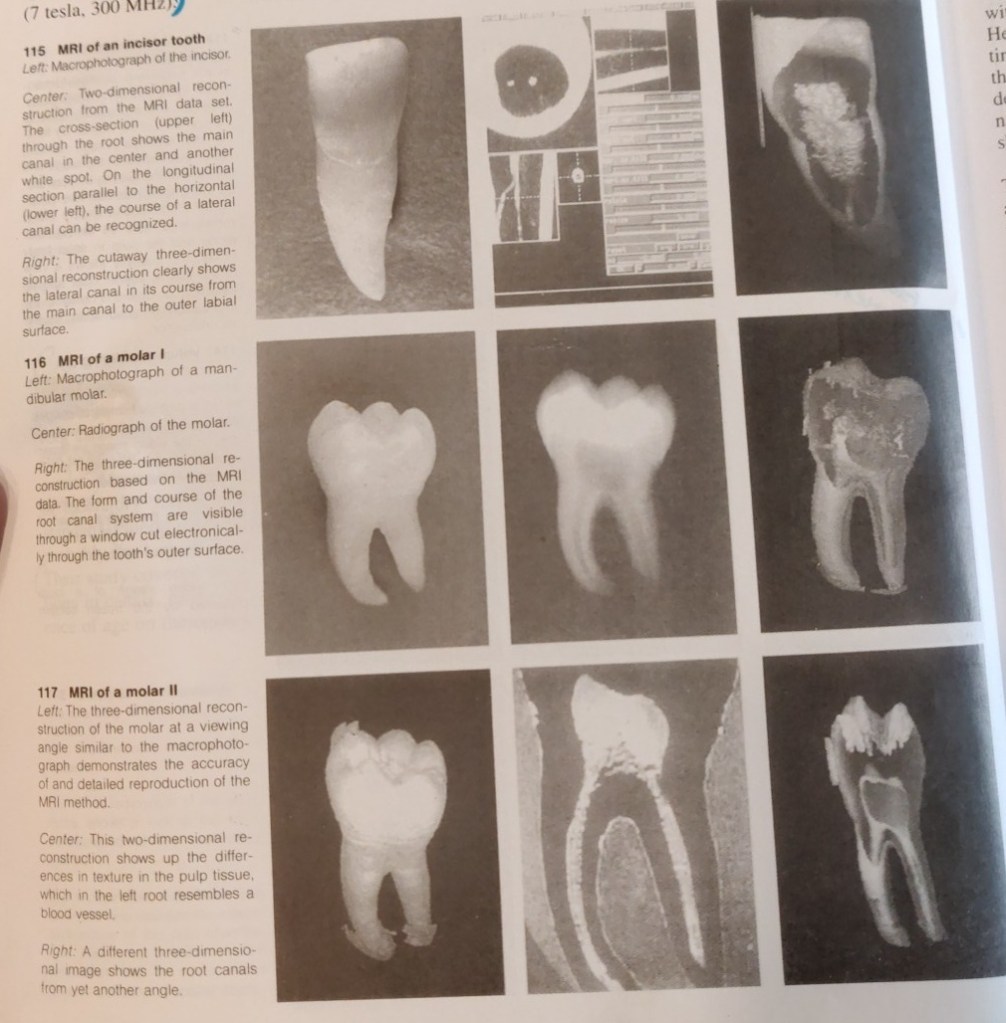

Normally, only vague images of bone and tooth can be obtained by magnetic resonance tomography (MRT). Baumann (1995; Baumann et al. 1993 a-d) was the first to succeed in producing a visual representation of the H+ protons of dental hard structures by using measurement sequences from solid body spectroscopy and especially strong magnetic fields. The soft pulpal tissue is elusive becuase of the small scale of the MRI. The first magnetic resonance images have now been realized with BRUKER SPECTOMETER AMX 300 WB (7 tesla, 300MHz).

Computer processing of data from the MRI permits creation of two and three-dimensional reconstructions that can be rotated and sectioned (Bauman 1995; Baumann and Doll, in press). Now for the first time we have a nondestructive method that does not use ionizing radiation. Two-dimensional sections of molars give rise to the hope that it will be possible to depict differences in tissue texture, which would be a great aid in the diagnosis of pulpitis. The spatial reconstruction of an individual canal configuration would be a great enlightment for endodontic treatment.

Reference – Color Atlas of Dental Medicine

ENDODONTOLOGY

Rudolf Beer, Michael A. Baumann, and Syngcuk Kim