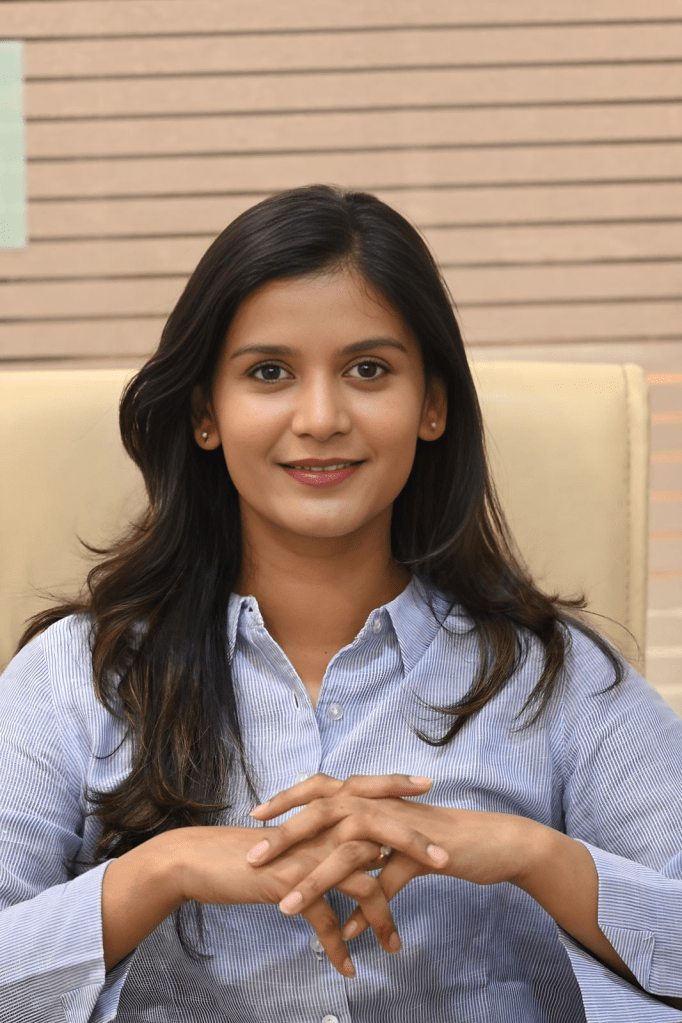

Picture this: a young dental student staring at a microscope, trying to figure out why her physiology textbook looks more like a foreign language manual than a path to making people smile. Enter Dr. Anukrati Srivastava—the woman who took that confusion, added a sprinkle of stubbornness, a dash of curiosity, and bam!—turned it into a dental career that makes patients beam and teachers proud. With an All India Rank of 97, a master’s degree, and an obsession with magnification and illumination, she’s not just treating teeth; she’s rewriting the rulebook on what it means to be a dentist who actually cares.

Think of her as the stand-up comedian of dentistry—only instead of punchlines, she delivers precision, patience, and those little “aha!” moments that make you go, “Wow, I never knew dental school could be like this.”

1) Can you share how your path in the dental profession began and the key milestones that shaped it?

My journey in dentistry began with a bit of resistance. During the first year, I wasn’t particularly interested, as the subjects like physiology and biochemistry seemed far removed from clinical dentistry. It didn’t feel relevant to what I wanted to do—treat patients and create smiles.

Everything changed in the third year when I joined a private clinic to experience dentistry beyond textbooks. That hands-on exposure taught me that dentistry is not just about treating teeth—it’s about patience, communication, and understanding the financial and emotional aspects of patient care.

A major milestone during my internship was preparing for the pre-PG exam. I began studying not just to pass, but to truly understand subjects and connect concepts. With guidance from exceptional teachers across India, patience, and consistent effort, I achieved AIR 97 and completed my master’s—a challenging journey that brought immense satisfaction.

Another pivotal moment came when I committed to performing all my cases under proper isolation, using magnification and illumination. I believe every dental student should use at least 3.5X magnification. Without it, you miss details that are crucial for becoming a better dentist.

2) What inspires you to stay passionate and committed to dentistry, even during challenging times?

I was fortunate to complete my bachelor’s and master’s at a prestigious institution—Govt. Dental College, Jaipur—with faculty who truly inspired me. Watching teachers work, understanding their thought process, and seeing their dedication to patients—not for money but for the joy of delivering excellent care—motivated me to push myself. Their example has been my anchor during challenging times, reminding me to always give my best.

3) Who is your role model in the dental field, and how has this person influenced your approach to patient care, academics, or professional growth?

While I’ve learned from many, I must mention Dr. Lalit Likhiyani and Dr. Manoj Aggarwal. They taught me to strive to be a better person every day and to deliver dentistry better than I did yesterday. During my student life, I often thought, “What would they say if they saw this?”—a question that drove me to excellence.

Academically, they never gave me straight answers. Instead, they asked more questions, encouraging me to explore literature, dig into articles, and develop reasoning. This approach instilled in me a love for learning and a habit of critical thinking.

4) Could you discuss the strategies you use to manage academic responsibilities alongside your personal interests or hobbies?

Balancing academics, clinical responsibilities, and personal life has been challenging. I realized early on the importance of prioritizing personal life. Some rules I follow include:

- No work calls after 7 PM.

- Weekly days off with my husband, who is also an orthodontist, with no appointments.

- Allocating time for House of Endodontics in my calendar.

- Maintaining an afternoon nap that I never compromise.

I also make time for painting, gardening with a cup of coffee, and long drives—simple joys that help me recharge. Sticking to a routine has been key to maintaining balance.

5) What advice would you give to current dental students and aspiring dentists?

Yes, dentistry is challenging. Yes, it requires patience and perseverance. Yes, you will be self-critical about your cases. But the satisfaction of growing, learning, and creating beautiful smiles makes it all worthwhile. Stay curious, embrace mentorship, and never stop improving.

Conclusion:

So, what’s the takeaway from Dr. Anukrati Srivastava’s story? Simple. Dentistry is tough, exams are tougher, and yes, sometimes your coffee might get cold while you’re deep in a case. But passion, perseverance, and a touch of sass can turn all that chaos into something magical.

She’s living proof that you can love what you do, learn endlessly, and still have time to sip your coffee, paint a masterpiece, or take a Sunday drive. If dental students remember one thing from her journey, let it be this: don’t just aim to fix teeth—aim to shine brighter than the overhead lamp in your operatory. And maybe, just maybe, make it look effortless while you’re at it.