Pathologic changes in gingivitis are associated with the presence of oral microorganisms attached to the tooth and perhaps in or near the gingival sulcus.

STAGE I GINGIVITIS: THE INITIAL LESION

The first manifestations of gingival inflammation are vascular changes consisting of dilated capillaries and increased blood flow. These initial inflammatory changes occur in response to microbial activation of resident leukocytes and the subsequent stimulation of endothelial cells. Clinically, this initial response of the gingiva to bacterial plaque is not apparent.

Changes can also be detected in the junctional epithelium and perivascular connective tissue at this early stage. For example, the perivascular connective tissue matrix becomes altered, and there is exudation and deposition of fibrin in the affected area. Also, lymphocytes soon begin to accumulate. The increase in the migration of leukocytes and their accumulation within the gingival sulcus may be correlated with an increase in the flow of gingival fluid into the sulcus.

The character and intensity of the host response determine whether this initial lesion resolves rapidly, with the restoration of the tissue to a normal state, or evolves into a chronic inflammatory lesion. If the latter occurs, an infiltrate of macrophages and lymphoid cells appears within a few days.

STAGE II GINGIVITIS: THE EARLY LESION

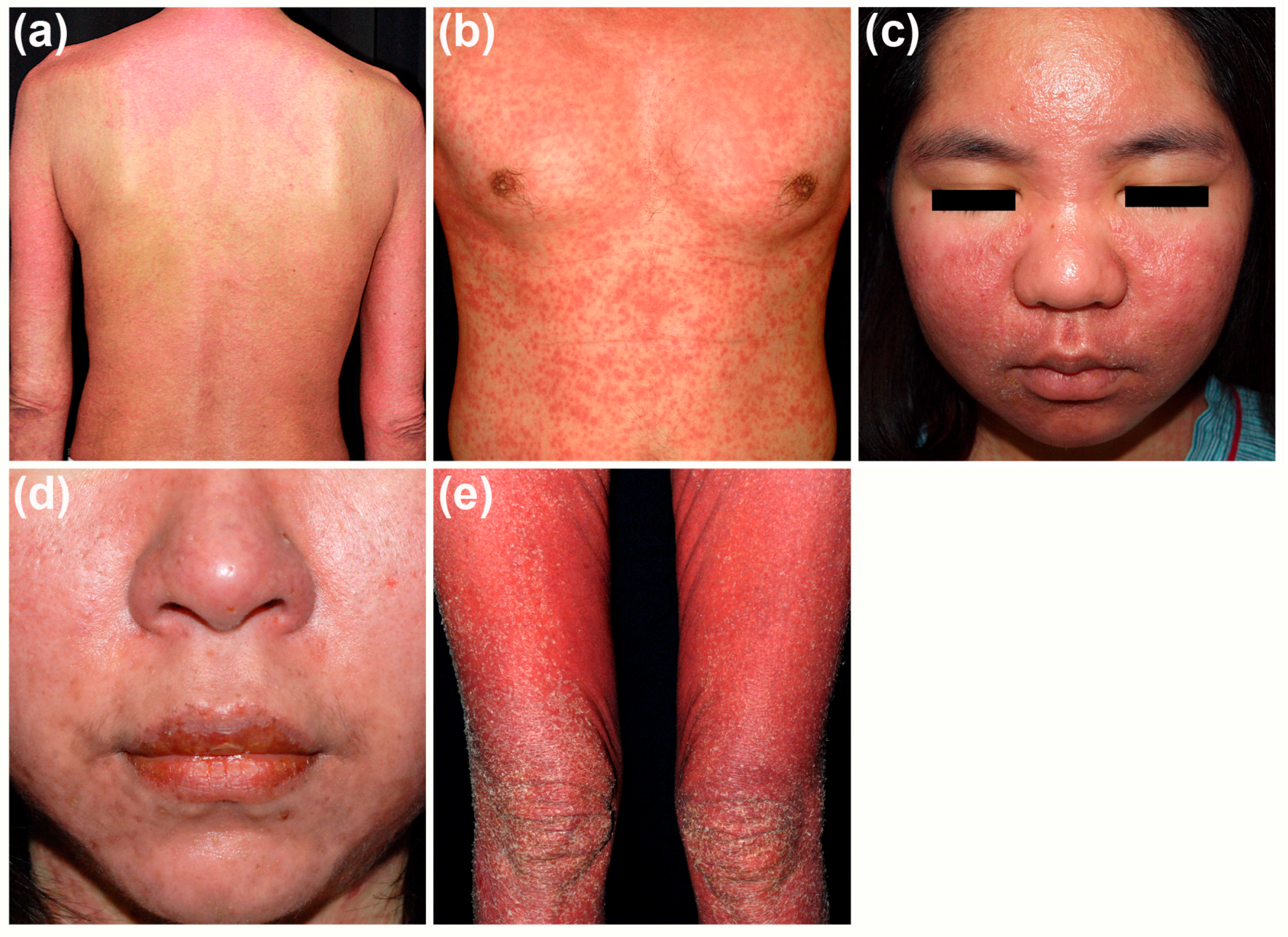

The early lesion evolves from the initial lesion within about 1 week after the beginning of plaque accumulation.Clinically, the early lesion may appear as early gingivitis, and it overlaps with and evolves from the initial lesion with no clear-cut dividing line. As time goes on, clinical signs of erythema may appear, mainly because of the proliferation of capillaries and increased formation of capillary loops between rete pegs or ridges . Bleeding on probing may also be evident.1 Gingival fluid flow and the numbers of transmigrating leukocytes reach their maximum between 6 and 12 days after the onset of clinical gingivitis.

The amount of collagen destruction increases 70% of the collagen is destroyed around the cellular infiltrate. The main fiber groups affected appear to be the circular and dentogingival fiber assemblies. Alterations in blood vessel morphologic features and vascular bed patterns have also been described.

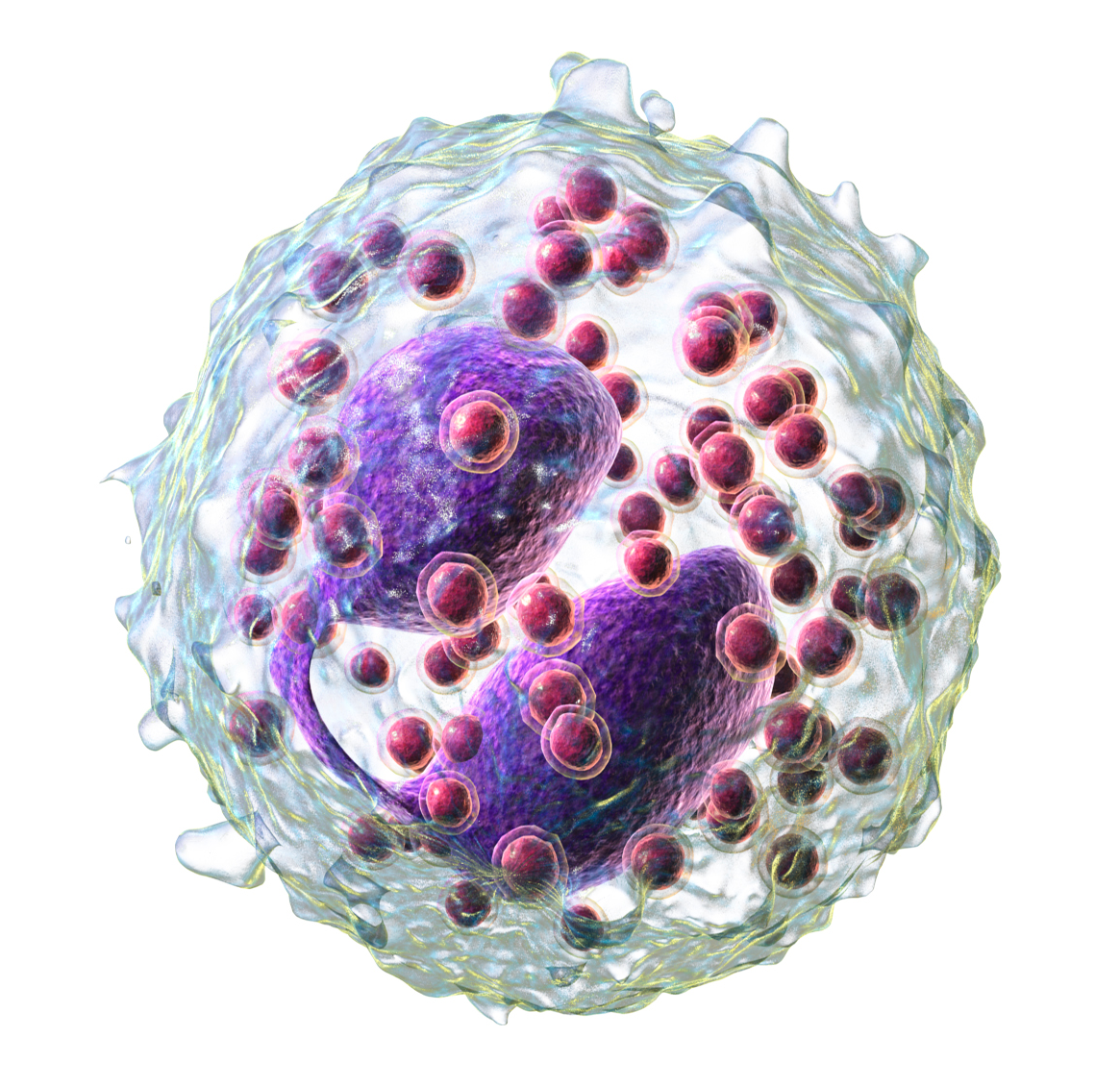

PMNs that have left the blood vessels in response to chemo- tactic stimuli from plaque components travel to the epithelium,

cross the basement lamina, and are found in the epithelium, emerg- ing in the pocket area. PMNs are attracted to bacteria and engulf them in the process of phagocytosis . PMNs release their lysosomes in association with the ingetion of bacteria.Fibroblasts show cytotoxic alterations, with a decreased capacity for collagen.

Meanwhile, on the opposite side of molecular events, collagen degradation is related to matrix metalloproteins (MMPs). Different MMPs are responsible for extracellular matrix remodeling within 7 days of inflammation, which is directly related to MMP-2 and MMP-9 production and activation.

STAGE III GINGIVITIS: THE ESTABLISHED LESION

Over time, the established lesion evolves, characterized by a predominance of plasma cells and B lymphocytes and probably in conjuncation with the creation of a small gingival pocket lined with a pocket epithelium.The B cells found in the established lesion are pre- dominantly of the immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and G3 (IgG3) subclasses.

In chronic gingivitis, which occurs 2 to 3 weeks after the beginning of plaque accumulation, the blood vessels become engorged and congested, venous return is impaired, and the blood flow becomes sluggish .The result is localized gingival anoxemia, which superimposes a somewhat bluish hue on the reddenedgingiva.18 Extravasation of erythrocytes into the connective tissue and breakdown of hemoglobin into its component pigments can also deepen the color of the chronically inflamed gingiva. The established lesion can be described as moderately to severely inflamed gingiva.

An inverse relationship appears to exist between the number of intact collagen bundles and the number of inflammatory cells.Collagenolytic activity is increased in inflamed gingival tissue17 by the enzyme collagenase. Collagenase is normally present in gingival tissues5 and is produced by some oral bacteria and by PMNs.

Enzyme histochemistry studies have shown that chronically inflamed gingivae have elevated levels of acid and alkaline phos- phatase, β-glucuronidase, β-glucosidase, β-galactosidase, esterases, aminopeptidase, and cytochrome oxidase. Neutral mucopolysaccharide levels are decreased, presumably as a result of degradation of the ground substance.

Established lesions of two types appear to exist; some remain stable and do not progress for months or years and others seem to become more active and to convert to progressively destructive lesions. Also, the established lesions appear to be reversible in that the sequence of events occurring in the tissues as a result of successful periodontal therapy seems to be essentially the reverse of the sequence of events observed as gingivitis develops. As the flora reverts from that characteristically associated with destructive lesions to that associated with periodontal health, the percentage of plasma cells decreases greatly, and the lymphocyte population increases proportionately.

STAGE IV GINGIVITIS: THE ADVANCED LESION

Extension of the lesion into alveolar bone characterizes a fourth stage known as the advanced lesion or phase of periodontal break- down.

Gingivitis will progress to periodontitis only in individuals who are susceptible. Patients who had sites with consistent bleeding had 70% more attachment loss than at sites that were not inflamed consistently (GI = 0). Teeth with noninflamed sites consistently had a 50-year survival rate of 99.5%, whereas teeth with consistently inflamed gingiva had a 63.4% survival rate over 50 years. Based on this longitudinal study on the natural history of periodontitis in a well-maintained male population, per- sistent gingivitis represents a risk factor for periodontal attachment loss and for tooth loss.

Reference- Caranza textbook of periodontology 11th edition