BY: Dr.Kriti Naja Jain :-

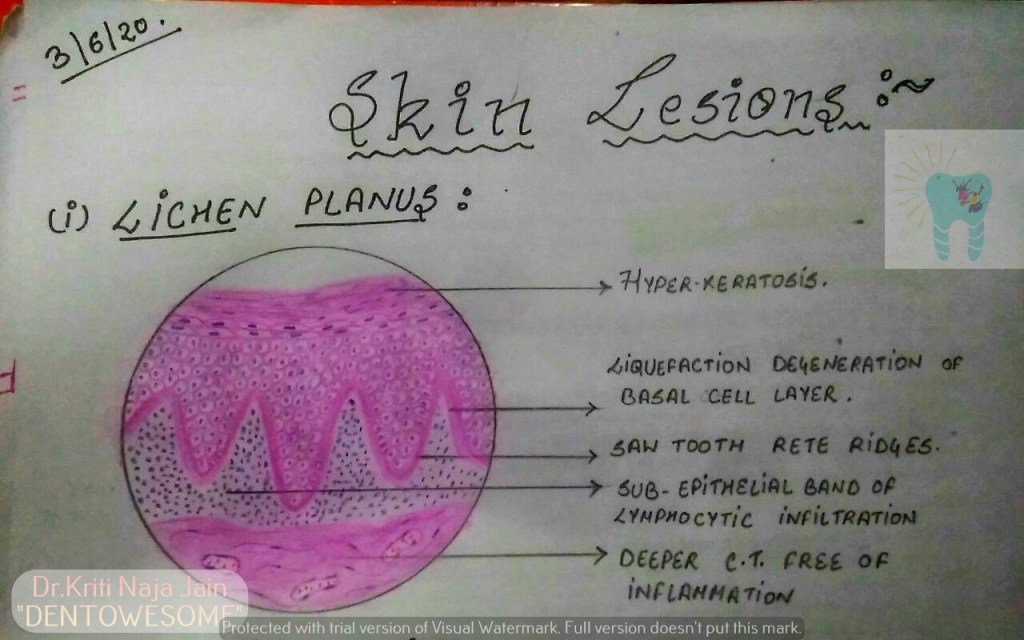

1.LICHEN PLANUS:-

*Lichen planus is a chronic mucocutaneous disorder manifested in a various forms in the oral cavity.

*The most characteristic pattern is” RETICULAR TYPE” with the interlacing white stripe called “WICKHAM’S STRIAE”.

*HISTOPATHOLOGY:-

- Histopathology FIRST DESCRIBED BY DUBRENILL 1906

- later revised by Shklar in 1972

- Hyper orthokeratinisation or hyper parakeratinisation

- ◦Thickening of granular layer

- ◦Acanthosis of spinous layer

- ◦Intercellular oedema in spinous layer

- ◦“ Saw-tooth” rete pegs

- ◦Liquefaction necrosis of basal layer- Max Joseph spaces

- ◦Civatte ( hyaline or cytoid) bodies

- ◦Juxta epithelial band of inflammatory cells

- ◦An eosinophilic band may be seen just beneath the basement membrane and represent fibrin covering lamina propria.

2.PEMPHIGUS :-

Pmphigus is a tissue specific autoimmune disease affecting the skin and mucosa. Clinical manifestations is in the from of “vesiculobullous lesions” that rupture to form ulcer and erosions .

*Vesiculobullous lesions develop due to immune mediated acantholysis causing intraepithelial vesicle formation.

*HISTOPATHOLOGY :-

- Formation of the vesicle or bullae within the epithelium that often results in a supra-basilar spilt or separation.

• Following this suprabasilar spilt in the epithelium, the basal cell layer remains attached to the lamina propria, and it often appears as a row-of-tomb stones.

• Loss of intercellular bridges and collection of edema fluid result in acantolysis within the spinus cell layer, which causes disruption of the prickle cells.

• As a result of acantholysis, clumps of large hyperchromatic epithelial cells desquamate that are often seen lying free within the vesicular fluid, these desquamated cells are often rounded and smooth in appearance and are known as “Tzanck cells”. - Small number of polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) and lymphocytes may be found within the vesicular fluid, but there is minimum inflammatory cell infiltration in the underlying connective tissue (unlike any other vesiculobullous lesion).

3.PEMPHIGOID :-

Pemphigoid is a vesiculobullous lesions that develop due to an autoimmune reaction directed against some components of basement membrane.

*This results in seperation of epithelium from the connective tissue with sub epithelial vesicles formation .

*Bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid are two different types of pemphigoid lesions.

*HISTOPATHOLOGY:-

- The inflammatory infiltrate is typically polymorphous, with an eosinophilic predominance.

- Mast cells and basophils may be prominent early in the disease course.

- Electron microscope shows basement membrane attached to the connective tissue rather than overlying separated epithelium.

- Tzanck smear shows only inflammatory cells.

- Sub epithelial vehicle formation.

- Intact epithelium without acantholysis.

REFERENCE:-

- Pic – Maji Josh 2nd edition