source – Nancy 13th edition

Cyclosporine therapy may cause gingival hyperplasia

Gingival growth occurs in patients taking phenytoin.

Patients with cardiac disease should receive dental treatment in minimal stressful environment. Anxiety,exertion and pain should be minimized.

Irregular pulse, engorged jugular veins and tachypnea may indicate the presence of cardiac disease.A history of hypertension, ischemic heart disease or any other cardiac problem particularly congenital heart disease and drug intake (anticoagulant, aspirin) should be sought.Angina may present as pain in the mandible, teeth and other oral Tissues Epinephrine in the local anesthesia may raise the blood pressure and precipitate dysarrhythmias.In patients with IHD, facilities for medical help, oxygen and nitroglycerine should be Available General anesthesia should be avoided for at least three months in patients with recent onset angina

Patient’s with Cushing’s syndrome more prone to get infections.(candidiasis)

Elective dental surgery should be deferred for 6 months following acute MI.Prophylaxis for infective endocarditis is mandatory in cases where there is a risk.Cardiac patients on anticoagulant drugs or aspirin are at increased risk of bleeding following dental procedures.Hence, these drugs should preferably be stopped a week before the procedure.Calcium channel blockers may cause gingival swelling and lichenoid lesions in the oral cavity. ACE inhibitorscan cause loss of taste, burning sensation in oral cavity,and angioedema. Dry mouth can result due toantihypertensive drugs such as d

Rifampicin can cause red saliva.

Elective dental care is avoided in patients with acuterenal failure

Elective dental procedures are better tolerated on non-dialysis days

Blood pressure measurement is advised at every visit.

Brown to black macular pigmentation in oral mucosa can be suspected for Addison disease.

Gonorrhea may present uncommonly with oral manifestations like tonsillitis, lymphadenitis, and painful oral and pharyngeal ulcers.

Oral manifestations in peptic ulcer disease are rare.However erosive dental lesions could be appreciated on lingual surface of lower incisors or palatal surface of upper maxillary teeth.

*Anatomically, the respiratory system divides into upper and lower respiratory tracts

Functionally, the respiratory system divides into conducting and respiratory portions

Moves (aka, conducts) air between the lungs and the outside environment.

Participates in gas exchange

Adenosine is used to treat supraventricular tachycardias; it slows or blocks conduction in the atrioventricular node.

– It’s important to know that theophylline (a common asthma medication) and caffeine reduce adenosine’s efficacy by blocking its receptors.

– Adenosine may trigger bronchospasm.

Magnesium ions are sometimes used to treat torsades de pointes and digoxin toxicity.

Potassium ions may be used in some patients to slow conduction and can suppress ectopic pacemakers.

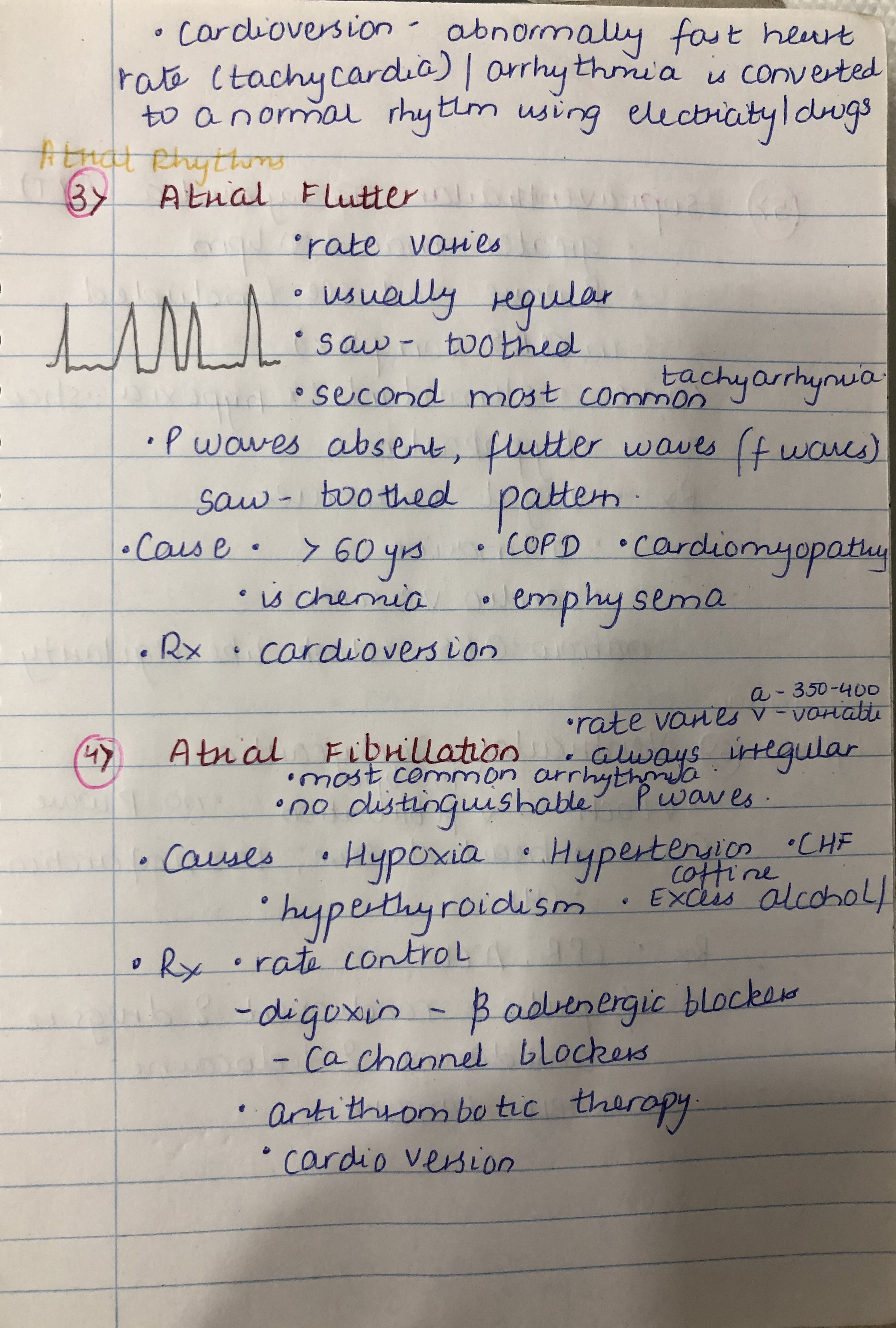

Digoxin can be used in some patients to treat atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation; it slows or blocks conduction in the atrioventricular node by inhibiting sodium-potassium ATPase.

– However, digoxin can cause ectopic arrhythmias, gastrointestinal and visual side effects, and breast enlargement (gynecomastia, in males), and has been associated with increased risk of breast and uterine cancer, likely due to its phyto-estrogen effects.

Review

Effects of Class 1 anti-arrhythmics on this curve

Class 1a

Class 1b

Class 1c

Symptoms

– Dyspnea upon exertion is a common early sign; it occurs because the heart cannot increase cardiac output despite increased metabolic demands.

– Orthopnea is characterized by dyspnea that occurs when lying flat, but is quickly relieved by sitting upright or standing; orthopnea occurs because the heart is unable to adjust to the redistribution of body fluids that occurs when lying flat.

– Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, as its name suggests, is characterized by sudden episodes of dyspnea that awaken a person after 1-2 hours of sleep, usually at night.

– Sleep-disordered breathing includes obstructive sleep apnea and Cheyne Stokes Respiration; show that Cheyne Stokes Respiration is characterized by cycling periods of tachypnea or hyperpnea alternating with periods of apnea.

– Other symptoms may also be present, often reflecting reduced cardiac performance; for example, patients may experience cognitive impairments, arrhythmias, cyanosis, or thrombi formation in the heart chambers.

Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF)

Dilated cardiomyopathy

– Genetic mutations, which often lead to defects in the cardiac myocyte cytoskeleton, sarcolemma, and nuclear envelope.

– Various infections, including Coxasackievirus, Chagas Disease, and HIV;

– Toxins and drugs, especially alcohol abuse, cocaine, and some cancer drugs.

– Metabolic disorders, including diabetes, hyper- or hypo-thyroidism, hyper- or hypo-kalemia, and various nutritional deficiencies.

– Neuromuscular diseases, such as Friedreich ataxia and muscular dystrophy.

– Pregnancy (the cardiomyopathy becomes apparent in late pregnancy or postpartum period).

– Myocarditis.

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Restrictive cardiomyopathy

Symptoms

ECG

Cardiac Biomarkers

Imaging Evidence

First 12 hours of myocardial infarction, cell death occurs.

– Coagulation necrosis begins, and cells spill their contents into the surrounding ECM.

– Microscopic changes include the appearance of “wavy fibers,” which are elongated myocardiocytes; their striations and nuclei become less apparent.

– The sarcolemma begins to malfunction, allowing the cell contents to spill.

– Results in edema and hemorrhaging, which further pushes the myocytes apart.

– Serum levels of key biomarkers, creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) and cardiac troponin I, begin to rise.

– Arrhythmia, which is the direct result of cardiomyocyte cell dysfunction, is the most common cause of death in the early hours after myocardial infarction.

12-24 hours after infarction, the inflammatory process dominates.

– Coagulation necrosis continues, and neutrophils and other pro-inflammatory leukocytes infiltrate and digest the necrotic tissues.

– Dark mottling of the myocardium may become visible.

– Creatine kinase-MB and cardiac troponin levels peak at approximately 24 hours after infarction.

3 days post-infarction, the processes of inflammation repair and tissue repair begins.

– This is marked by a shift from pro-inflammatory cells to apoptotic neutrophils and phagocytic macrophages.

– Macrophages phagocytose the dying neutrophils as well as the necrotic tissue debris.

– In a gross image, we would see the development of a hyperemic border with a yellow-tan center at the area of the infarct.

– Pericarditis most commonly occurs around days 2 and 3 after infarct; it may be characterized by chest pain or an audible friction rub upon auscultation.

7 days post-infarct, phagocytic debris removal continues and granulation tissue begins to appear.

– Granulation tissue comprises proliferating myofibroblasts, loose collagen fibers, and newly forming capillaries and vascular tissues.

– In a gross image, show that we would see a hyperemic border with central softening, with a yellow appearance.

– Because of this softening in the myocardium, the risk of cardiac rupture is highest around days 4-7; rupture can involve a free wall, as we’ve shown in our illustration, or in a septum or papillary muscle.

Learn more

10-14 days Granulation tissue starts to replace the yellow necrotic tissue; collagen deposition for scar formation begins.

Weeks 2-8: grayish-white scar tissue develops from out outside border inwards towards the core.

– Dressler syndrome may develop; this is a delayed form of pericarditis thought to be caused by an autoimmune reaction.

3-6 months: a mature scar characterized by dense collagen occupies the area of infarction.

– True ventricular aneurysm is a potential late complication, in which the thin, scarred area of the heart wall bulges during systole; this can lead to heart failure, arrhythmias, or other complications.