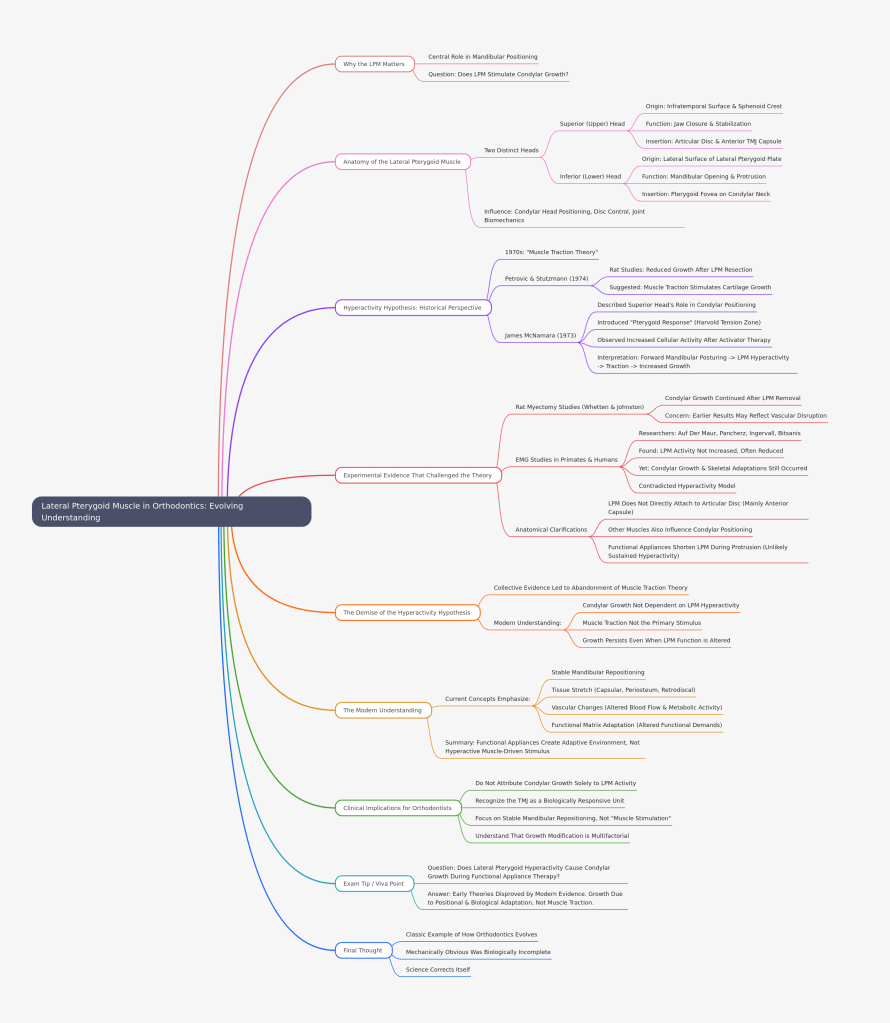

In orthodontics, few topics have sparked as much debate as the role of the lateral pterygoid muscle (LPM) in functional appliance therapy. Once considered the prime driver of condylar growth through “hyperactivity,” the LPM has since undergone a scientific re-evaluation.

Let’s explore how our understanding evolved.

Why the Lateral Pterygoid Matters

The LPM plays a central role in mandibular positioning, particularly during protrusive and lateral movements. Because functional appliances posture the mandible forward, early researchers naturally questioned:

Does the lateral pterygoid muscle stimulate condylar growth through traction?

To understand the controversy, we must first revisit its anatomy.

Anatomy of the Lateral Pterygoid Muscle

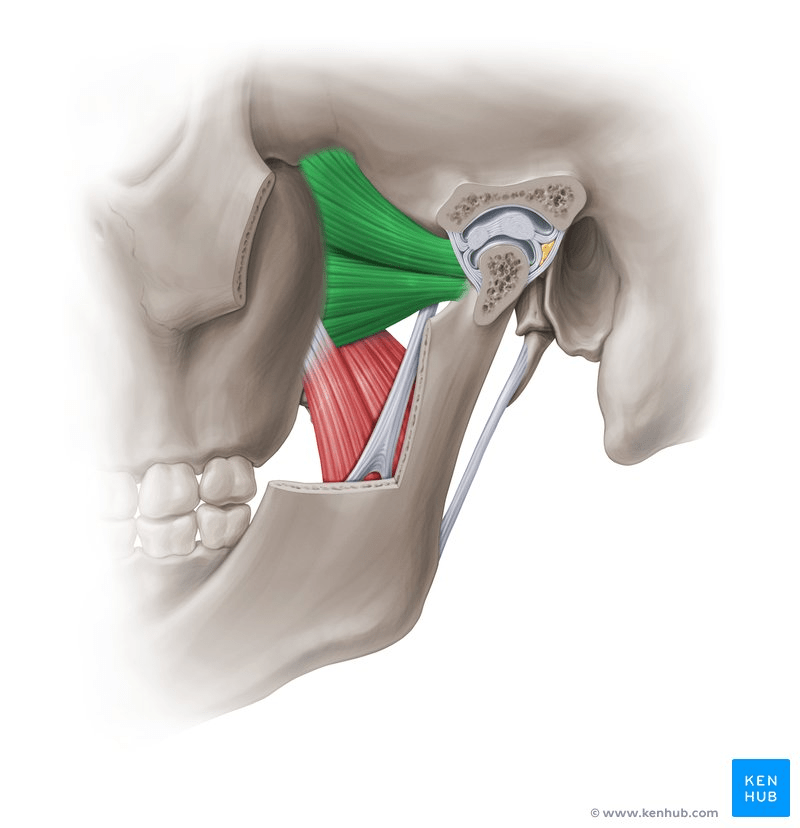

The LPM has two distinct heads:

🔹 Superior (Upper) Head

- Origin: Infratemporal surface and crest of the greater wing of the sphenoid

- Function: Active during jaw closure and stabilization

- Insertion: Primarily into the articular disc and anterior capsule of the TMJ

🔹 Inferior (Lower) Head

- Origin: Lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plate

- Function: Active during mandibular opening and protrusion

- Insertion: Pterygoid fovea on the condylar neck

Both heads converge posteriorly and influence condylar head positioning, disc control, and joint biomechanics.

The Hyperactivity Hypothesis: A Historical Perspective

In the 1970s, the “muscle traction theory” dominated thinking.

🔬 Petrovic & Stutzmann (1974)

- Rat studies showed reduced condylar growth after LPM resection.

- Suggested that muscle traction stimulates condylar cartilage growth.

📚 James McNamara (1973)

- Described the role of the superior head in condylar positioning.

- Introduced the concept of the “Pterygoid Response” (also called the Harvold Tension Zone).

- Observed increased cellular activity above and behind the condyle following activator therapy.

The interpretation?

Forward mandibular positioning → LPM hyperactivity → Traction on condyle → Increased growth.

It seemed biologically elegant and mechanically convincing.

Experimental Evidence That Challenged the Theory

Science, however, demands replication and scrutiny.

🧪 Rat Myectomy Studies (Whetten & Johnston)

- Condylar growth continued even after LPM removal.

- Raised concerns that earlier results may have reflected vascular disruption rather than true traction effects.

📈 EMG Studies in Primates and Humans

Researchers such as:

- Auf Der Maur

- Pancherz

- Ingervall

- Bitsanis

found that during functional appliance therapy:

- LPM activity was not increased

- In many cases, LPM activity was actually reduced

- Yet condylar growth and skeletal adaptations still occurred

This contradicted the hyperactivity model.

Anatomical Clarifications

Further anatomical studies revealed:

- The LPM does not directly attach to the articular disc as previously thought.

- Its attachment is mainly to the anterior capsule, not firmly to the disc.

- Other muscles (temporalis, masseter) also influence condylar positioning.

- Functional appliances actually shorten the LPM during protrusion, making sustained hyperactivity biomechanically unlikely.

This was a critical turning point.

The Demise of the Hyperactivity Hypothesis

The collective evidence led to abandonment of the muscle traction theory.

Today we understand:

✔ Condylar growth is not dependent on LPM hyperactivity

✔ Muscle traction is not the primary stimulus

✔ Growth persists even when LPM function is altered

So what explains the skeletal changes?

The Modern Understanding

Current concepts emphasize:

🔹 Stable Mandibular Repositioning

Forward posturing alters spatial relationships within the TMJ.

🔹 Tissue Stretch

Capsular tissues, periosteum, and retrodiscal tissues experience adaptive stretch.

🔹 Vascular Changes

Altered blood flow and metabolic activity contribute to remodeling.

🔹 Functional Matrix Adaptation

Growth is influenced by altered functional demands, not isolated muscle traction.

In short:

Functional appliances create an adaptive environment — not a hyperactive muscle-driven stimulus.

Clinical Implications for Orthodontists

For postgraduate students and clinicians:

- Do not attribute condylar growth solely to LPM activity.

- Recognize the TMJ as a biologically responsive unit.

- Focus on stable mandibular repositioning rather than “muscle stimulation.”

- Understand that growth modification is multifactorial — muscular, skeletal, vascular, and biomechanical.

Exam Tip / Viva Point

If asked:

“Does lateral pterygoid hyperactivity cause condylar growth during functional appliance therapy?”

Answer:

Early theories supported this view, but modern experimental and EMG evidence disproves it. Condylar adaptation occurs despite reduced LPM activity, suggesting growth is due to positional and biological adaptation rather than muscle traction.

Final Thought

The story of the lateral pterygoid muscle is a classic example of how orthodontics evolves.

What once seemed mechanically obvious was biologically incomplete.

And that’s the beauty of science — it corrects itself.