Every orthodontic student eventually faces one of the toughest decisions in treatment planning — what to do with borderline Class III malocclusion cases. These are patients whose skeletal discrepancy is neither mild enough for camouflage nor severe enough to demand immediate orthognathic surgery. So, how do we decide?

A landmark study by A-Bakr Rabie and colleagues (2008) explored exactly this question, comparing treatment outcomes of orthodontic camouflage (extraction-based) and orthognathic surgery in borderline Class III patients.

The Study at a Glance

- Sample: 25 Southern Chinese adults

- 13 treated orthodontically (extraction protocol)

- 12 treated surgically (bimaxillary or mandibular setback)

- Selection criteria: Pretreatment ANB > −5°, with clear Class III skeletal tendency.

- Aim: Identify cephalometric differences and outcomes between the two treatment paths.

| Parameter | Camouflage (Orthodontic) | Surgery |

|---|---|---|

| ANB angle | > –5° | ≤ –5° |

| Holdaway angle | > 12° ✅ | < 12° 🚩 |

| Wits appraisal | > –7.5 mm | < –7.5 mm |

| Go-Me / S–N ratio | ~111 | ↑ 119 |

| U1–L1 angle | ↓ (≈120°) | ↑ (≈129°) |

Previous research (https://dentowesome.org/2025/11/12/class-iii-malocclusion-surgery-or-orthodontics/) tried to give us some hard rules. Kerr suggested that if the ANB angle is less than -4°, go surgical. Stellzig-Eisenhauer threw a whole formula at us using four variables. But honestly? These didn’t really help us distinguish between the borderline cases. It turns out, this research paper discovered something much more practical.

Key Finding — The Magic Number: Holdaway Angle

Among the many cephalometric parameters analyzed, the Holdaway angle stood out as the best predictor for treatment modality.

🔹 Holdaway angle ≥ 12° → Orthodontic camouflage likely to succeed

🔹 Holdaway angle < 12° → Orthognathic surgery indicated

This single angle correctly classified 72% of the cases — making it a practical clinical guide for borderline cases.

How the Two Treatments Differed

| Aspect | Camouflage (Extraction) | Orthognathic Surgery |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Retraction of lower incisors + downward/backward mandibular rotation | Surgical setback of the mandibular dentoalveolus |

| Cephalometric effects | ↓ L1–ML angle (retroclined incisors) | ↑ L1–ML angle (uprighting) |

| Facial changes | Increased lower facial height; improved profile via dental compensation | Setback of chin and lower lip, harmonious soft-tissue correction |

| Soft tissue | No significant difference post-treatment between groups | Comparable esthetic improvements |

Both treatments target the lower dentoalveolus, emphasizing incisor position and mandibular rotation.

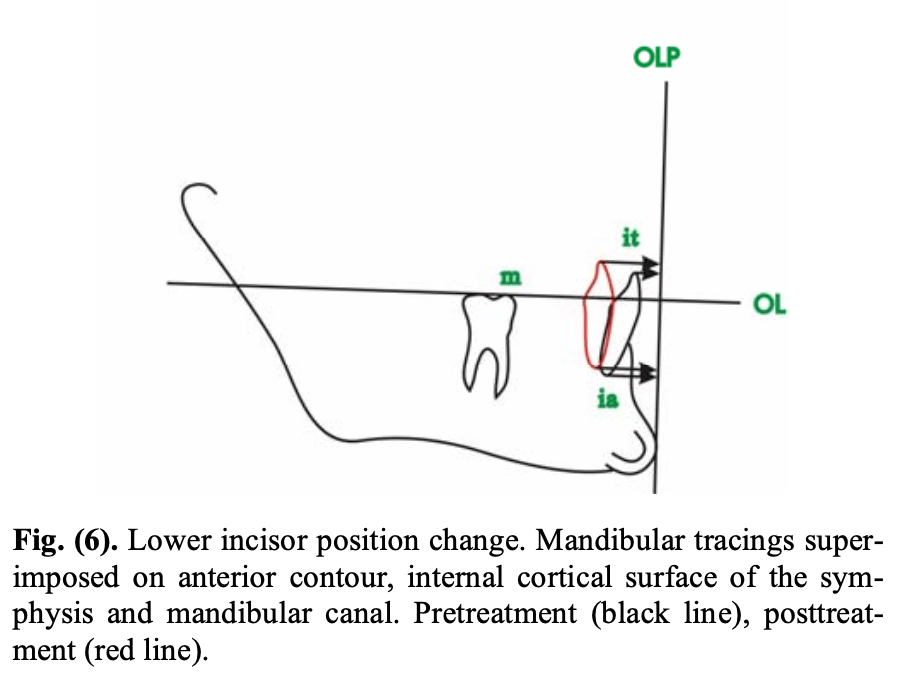

The orthodontic group in this study retracted the lower incisors by an average of 4.9 mm at the incisal tip and 1.9 mm at the incisor apex. That’s not a typo—the roots barely moved. Why? Because you’re using lingual root torque to prevent the incisors from tipping back excessively. You want to maintain incisor inclination while achieving anterior-posterior movement.

In Short

Holdaway angle ≈ 12° may be your cephalometric compass when planning for borderline Class III cases —

but the final direction still depends on your patient’s goals and your clinical judgment.

Rabie A.-B.M., Wong R.W.K., Min G.U. (2008). Treatment in Borderline Class III Malocclusion: Orthodontic Camouflage (Extraction) Versus Orthognathic Surgery.

The Open Dentistry Journal, 2:38–48. DOI: 10.2174/1874210600802010038.