Author: Kerr W.J.S., Miller S., Dawber J.E.

Journal: British Journal of Orthodontics (1992)

🎯 Why This Topic Matters

Every orthodontic student eventually faces this critical question:

When does a Class III malocclusion cross the line from orthodontic correction to surgical intervention?

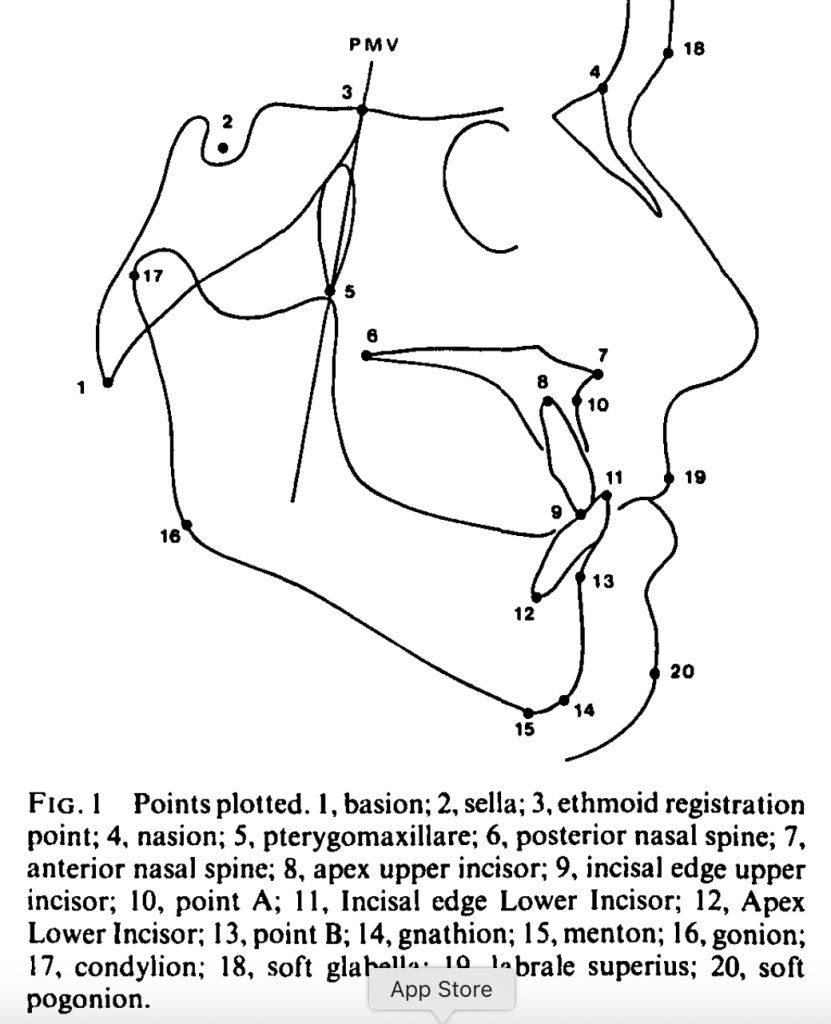

Understanding this boundary is essential—not only for diagnosis and treatment planning but also for effective communication with patients and surgical colleagues. The study by Kerr and colleagues provides timeless, cephalometrically based guidance that remains clinically relevant even today.

🦷 The Study in a Snapshot

The researchers compared two groups of 20 patients with severe Class III malocclusion:

- Group 1: Treated with orthodontics alone

- Group 2: Recommended for orthognathic surgery

All patients had negative overjets, ensuring comparable skeletal severity.

📈 Key Cephalometric Findings

| Parameter | Surgery Group (Mean) | Ortho Group (Mean) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANB Angle | -6.9° | -2.6° | p < 0.001 |

| M/M Ratio (Maxilla/Mandible Length) | 0.78 | 0.89 | p < 0.001 |

| Lower Incisor Inclination | 78.5° | 85.4° | p < 0.01 |

| Holdaway Angle | 0.9° | 6.1° | p < 0.01 |

These four parameters clearly differentiated surgical from orthodontic cases.

What About Vertical Dimensions and Overbite?

Surprisingly, vertical measurements like facial proportions, gonial angle, or Y-axis didn’t strongly differentiate surgical cases from orthodontic ones in this study. Nor was an open bite tendency common. So while vertical control is important in treatment, it might not be the clincher in Class III treatment decisions.

🧩 What These Numbers Mean Clinically

Kerr et al. proposed “threshold values”—practical cut-offs to guide treatment choice:

| Cephalometric Parameter | Threshold Value Suggesting Surgery |

|---|---|

| ANB Angle | ≤ -4° |

| Lower Incisor Inclination (IMPA) | ≤ 83° |

| Holdaway Angle | ≤ 3.5° |

| M/M Ratio | ≤ 0.84 |

🦷 Interpretation:

If your patient’s ANB is more negative than -4° and the lower incisors are retroclined below 83°, it’s likely beyond orthodontic camouflage. Surgical correction—usually mandibular setback or bimaxillary surgery—is indicated.

🧠 The Soft Tissue Factor

An underrated but critical insight from the study:

The soft tissue profile often drives the decision more than skeletal numbers.

Even if occlusion could be camouflaged, an unattractive concave profile or reduced Holdaway angle may push the decision toward surgery for facial balance and esthetics.

📚 Final Thoughts

This 1992 study by Kerr et al. remains a cornerstone for understanding the borderline Class III dilemma. It reinforces that:

Good orthodontics begins with good diagnosis—and great orthodontists know when to call the surgeon.

So, the next time you evaluate a challenging Class III case, remember these cephalometric yardsticks. They just might help you make the right call between brackets and bone cuts.