When orthodontists treat unerupted or impacted teeth (especially in the anterior region), several complications can occur:

- Tooth devitalization (loss of vitality)

- Re-exposure or uncovering after surgery

- Ankylosis (tooth fused to bone)

- External root resorption

- Damage to adjacent teeth

- Marginal bone loss

- Gingival (gum) recession

➡️ These complications can prolong treatment, cause esthetic problems, and even lead to tooth loss.

Why These Problems Happen

Historically, clinicians focused on surgically exposing the tooth (“uncovering”) to bring it into the arch.

However, the soft tissue (gingiva) around the tooth was often not given enough attention.

Most early surgical techniques, such as “simple complete exposure,” focused only on getting to the tooth, without considering:

- What kind of mucosa (attached gingiva vs. alveolar mucosa) covered it

- How that tissue would behave once orthodontic movement began

Why Soft Tissue Type Matters

There are two main kinds of oral mucosa:

- Attached gingiva (masticatory mucosa):

- Firm, tightly bound to bone

- Designed to resist mechanical stress and prevent muscle pull on the gum margin

- Ideal marginal tissue around a tooth

- Alveolar mucosa:

- Movable, thin, and elastic

- Poor at resisting muscle pull or inflammation

- Not suitable as a marginal tissue

If a tooth is uncovered and surrounded only by alveolar mucosa, the tissue tends to get inflamed easily, which can lead to bone loss and gingival recession as the tooth is moved orthodontically.

What the Ideal Surgical Approach Should Do

Instead of just exposing the tooth, the surgical goal should be to:

- Ensure that a band of attached gingiva surrounds the crown once the tooth is exposed.

- Create a healthy, functional marginal tissue environment before starting tooth movement.

This provides several key advantages:

- Prevents the need for repeated dressings or barriers to keep the tooth exposed

- Allows faster and smoother tooth movement (no soft-tissue obstruction)

- Prevents gingival recession and bone loss during orthodontic traction

Why Inflammation Is a Risk Factor

Periodontal experience shows that tooth movement in the presence of inflammation is risky — it can accelerate bone loss.

Since alveolar mucosa is prone to inflammation, it’s unsafe to move a tooth unless it’s surrounded by healthy attached gingiva.

Thus, the uncovering procedure must integrate periodontal principles — ensuring that the final gingival condition supports tooth health and stability.

ORTHODONTIC CONSIDERATIONS BEFORE SURGERY

Why create space before uncovering the tooth?

There are two main reasons:

- For eruption and alignment:

- If adequate space isn’t available in the arch, the unerupted tooth has no place to move into.

- So, before any surgical exposure, orthodontic space creation ensures there’s enough room for the tooth to erupt or be moved into proper alignment.

- For surgical soft-tissue management:

- The edentulous (toothless) space left in the arch is covered by attached gingiva, which can be used as a donor site.

- This tissue can then be repositioned apically or laterally as a partial-thickness flap to cover the exposed tooth crown after surgery — ensuring the presence of healthy, attached gingiva around the tooth.

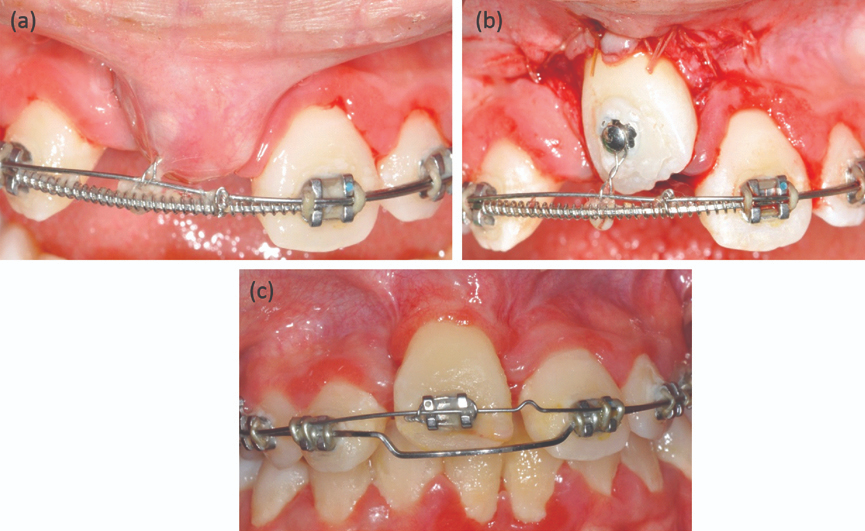

SURGICAL PROCEDURE: STEP-BY-STEP LOGIC

Anesthesia and incision:

- Local infiltration anesthesia is administered.

- The surgeon makes an incision along the ridge in the edentulous area — where the impacted tooth lies beneath.

Determining incision design:

- The height (incisogingival dimension) of the incision depends on how much attached gingiva is present on the adjacent teeth or its opposite tooth (antimere).

- If there’s plenty of attached gingiva nearby, a larger flap can be created and repositioned.

Flap elevation and bone removal:

- Vertical releasing incisions are made to free the attached gingiva.

- Connective tissue over the unerupted tooth is gently removed.

- Bone is removed only up to the height of contour of the crown, not beyond the cementoenamel junction (CEJ).

⚠️ Why stop at the CEJ?

Because this is the zone where the dentogingival attachment (junctional epithelium + connective tissue attachment) naturally forms.

If bone is removed beyond the CEJ, it can disrupt this zone and increase the risk of gingival recession — something confirmed in animal (monkey) studies.

PLACEMENT OF ATTACHED GINGIVA (THE GRAFT STEP)

Where and why to place it:

- The graft (attached gingiva) is positioned to cover:

- The CEJ, and

- About 2–3 mm of the crown.

This positioning serves three biologic and mechanical purposes:

- Establishing stable attachment:

- It helps form a healthy supra-alveolar connective tissue attachment between the tooth root (cementum) and alveolar bone.

- This ensures periodontal stability and prevents bone loss.

- Creating a proper epithelial seal:

- Masticatory mucosa (keratinized attached gingiva) provides a strong, protective epithelial barrier.

- This seal prevents bacterial ingress and inflammation — something alveolar mucosa cannot achieve.

- Allowing safe tooth movement:

- As the tooth is orthodontically pulled into the arch, tension develops in the gingiva.

- If the gingiva is attached higher (more coronally), it can accommodate slight apical repositioning during movement without losing its protective role.

- In simpler terms — the gum margin “moves with the tooth” instead of receding.

POST-SURGICAL STEPS

- Sutures are placed on both sides (mesial and distal) to hold the graft stable over the tooth.

- A periodontal dressing is placed for 7–10 days to protect the surgical site and allow:

- Reattachment of the tissue to the tooth

- Epithelial healing over the area

- Once the dressing is removed:

- A bonded orthodontic bracket is attached directly to the tooth.

- Light orthodontic forces are applied immediately to begin eruption or alignment.

🔑 Light force is critical — it allows physiologic movement without jeopardizing the new soft tissue attachment.

Why This Method Works Better

The described surgical exposure technique (with attached gingiva placement) is particularly advantageous for teeth with delayed or retarded eruption.

It provides both biologic and mechanical benefits that improve eruption success and tissue health.

What Actually Delays Eruption: Bone or Soft Tissue?

- Traditionally, it was thought that bone acts as the main physical barrier delaying eruption.

- However, clinical and biologic observations show that this is not true unless the tooth is ankylosed (fused to bone).

👉 The rate of bone remodeling (turnover) is actually faster than the rate of remodeling in the overlying soft tissue.

➡️ Therefore, the soft tissue — not the bone — is often the main factor that slows eruption or impedes tooth movement.

Managing Long-Distance Tooth Movement

When a tooth has to travel a large distance to reach the arch:

- The surrounding gingiva may begin to “bunch up” as the tooth moves.

- In such cases, minor excision of excess tissue may be required to achieve:

- Ideal gingival contour,

- Correct tooth positioning,

- Long-term posttreatment stability.

The key to managing delayed eruption lies not in removing more bone but in controlling and reconstructing the soft tissue environment.

Creating a zone of attached gingiva around the uncovered tooth transforms the biologic response, allowing stable eruption and long-term periodontal integrity.