Let’s talk about anterior maxillary osteotomy—a fancy way of saying “pushing your upper jaw back into place because your teeth decided to go rogue.” Now, before we dive into the nitty-gritty, let’s acknowledge the real heroes here: the orthodontists and surgeons who spend their days nudging bones like a very sophisticated game of Jenga.

Maxillary osteotomies have been around longer than your grandma’s secret recipe for laddoos. But unlike her kitchen skills, these techniques come with scalpels, screws, and a significant chance of making your nose twitch for weeks.

We have three classic moves in the Maxillary Osteotomy Dance:

1. Wassmund osteotomy – Named after a guy who probably spent too much time thinking about cutting bones.

2. Wunderer osteotomy – Wunderer…because wondering if your face will move correctly afterward is part of the thrill.

3. Anterior maxillary downfracture osteotomy – For those who like their surgery with a side of gravity.

While all three techniques get the job done, they differ in their “access route”, like Google Maps giving you three ways to get to the same dental conference—one scenic, one straightforward, and one with a questionable dirt road.

The Problem With Pushing Forward

Now, if you thought moving the anterior maxilla forward was easy, think again. The palatal mucosa is like an overprotective mother—it does not stretch easily. If you try too hard, you might end up with an oronasal or oroantral fistula. (For those unfamiliar, that’s a fancy way of saying, “Congratulations, you now have an accidental bonus airway!”)

In fact, the only reported case of maxillary advancement via osteotomy happened in 1968—shoutout to William Bell, the original maxillary daredevil. He moved the maxilla forward, bone-grafted the leftover gap, and then—because 1968 was a wild time—popped in a removable denture like a dental Band-Aid.

Enter Distraction Osteogenesis – The Slow and Steady Approach

The dental world eventually realized that gradual movement is the way to go (kind of like convincing your cat to take a bath). So, we borrowed a trick from orthopedics: distraction osteogenesis. Originally developed for cleft lip and palate cases, this technique slowly moves bones using:

External distractors – Big, bulky, and very “Mad Max.”

Orthodontic face masks – Like Invisalign’s overachieving cousin.

Internal distractors – The discreet VIP section of distraction devices.

But here’s the twist: these are mostly used to move the whole maxilla forward (Le Fort I style), rather than just the anterior segment. That’s like moving an entire apartment building when all you really needed was to shift the balcony.

The Unexpected Hero: The Palatal Distractor

Palatal distractors have traditionally been used for expansion, helping kids (and the occasional brave adult) widen their maxilla to correct collapsed buccal occlusion. But someone (probably while holding a coffee and staring at a dog study) thought, “Hey, what if we used this thing to move the maxilla forward?”

The results?

Tooth-borne distractors were tested on dogs (lucky them), and they did successfully move the anterior maxilla forward—along with a lot of dental movement.

Bone-borne distractors came in to save the day, ensuring that actual bone (not just teeth) was being moved.

And guess what? There’s exactly ONE reported case of a palatal distractor being used to advance a retruded maxilla in a non-cleft patient. Just one. That’s rarer than an orthodontist who doesn’t own at least three pairs of loupes.

Who Needs This? (Besides People Who Want to Look Like Their Own X-Ray)

This technique is perfect for patients with maxillary hypoplasia in both the anteroposterior and transverse planes—especially if they have cleft lip and palate. Think of it like a strategic battlefield move:

Crossbite limited to anterior and premolars? Check.

Molars behaving themselves in normal buccal occlusion? Check.

Dental crowding making your orthodontist sigh dramatically? Check.

The beauty of this approach? As your maxilla gradually advances, new bone forms in its wake—meaning your displaced teeth can be politely guided into their new positions with post-surgical orthodontics.

The Surgical Game Plan: Step-by-Step (or Slice-by-Slice)

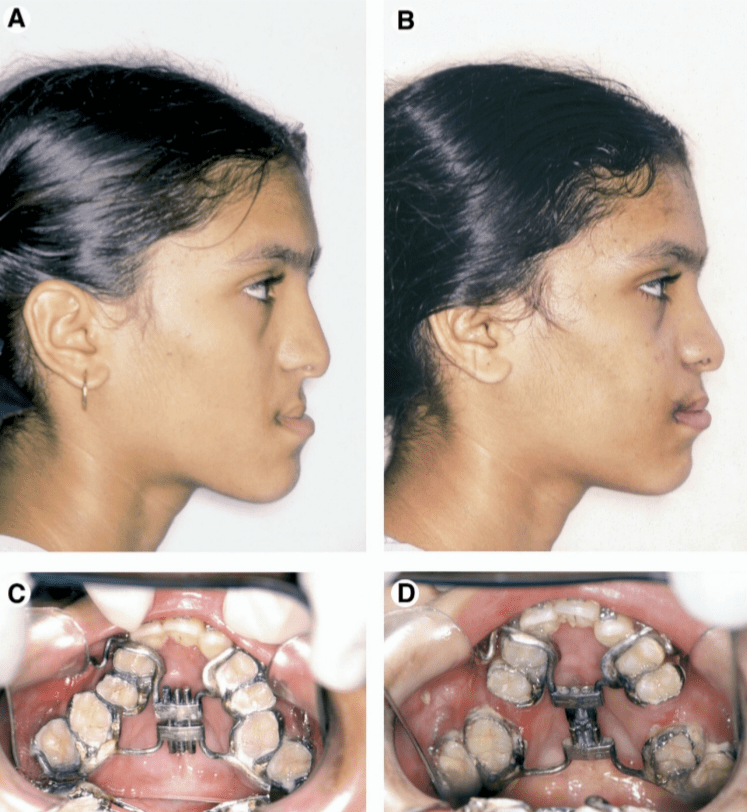

Step 1: Build Your Secret Weapon – The Hyrax Appliance

Before the surgery even starts, we need our mechanical hero: the Hyrax orthodontic appliance (which sounds like a prehistoric creature but is actually a German-made expansion screw). Unlike its usual role in expanding palates sideways, we tweak it to push forward instead of out.

4 arms of the appliance:

2 anterior arms → Soldered to canines or first premolars

2 posterior arms → Soldered to first or second molars

This is the equivalent of securing a medieval battering ram before storming the castle walls.

Step 2: Knock Knock, It’s Surgery Time!

Under general anesthesia (because no one wants to be awake for this), we begin:

1. Vestibular incision – From first molar to first molar (basically, a wide front door for the maxilla).

2. Mucoperiosteal flap reflection – Peeling back the gums like opening a well-wrapped gift… but with scalpels.

3. Buccal linear osteotomy – A clean cut above the maxillary teeth from pyriform rim to distraction site.

4. Lateral nasal wall cut – Because your nose needs to be in on the action too.

5. Septal osteotomy – The nasal septum gets a trim at its base (like a very aggressive haircut).

At this point, your maxilla is thinking, “What did I do to deserve this?”

Step 3: The Grand Downfracture (Because Upfracturing Isn’t a Thing)

Vertical interdental osteotomy → First, a light cut through the buccal cortex, then deepened carefully (like slicing a layered cake).

Palatal osteotomy → Extending the cut medially to separate the segment without puncturing the palatal mucosa (because who needs a hole in their mouth?).

Downfracturing the anterior maxilla → A gentle wiggle and push to mobilize it forward (think of convincing a cat to move off your laptop).

Important Rule: Do not mess with the palatal mucosal pedicle—it’s keeping everything alive!

Step 4: Installing the Hyrax & Hitting the Snooze Button

1. Cement the appliance onto the selected teeth. (Your maxilla is now officially in a mechanical relationship.)

2. Close the surgical wound. (Because we don’t want to leave things open-ended.)

3. Let the bone chill for five days. (Surgery is tiring. Even for your face.)

Step 5: The Big Move – Slow & Steady Wins the Maxilla Race

On post-op day five, we start activating the Hyrax:

1mm per day (Because bones like to take their time).

2 to 4 activation rhythms per day (Like an orthodontic drumbeat).

The anterior maxilla keeps moving forward until a normal overjet is achieved.

Once it’s in place? Lock it in for 6 weeks—because good things take time (and so does new bone formation).

The Good, The Bad & The Orthodontist Who Has to Deal With It

✅ The Benefits:

⭐ No need for bone grafts – Your body does all the hard work.

⭐ Improved soft tissue support – Upper lip & paranasal area get a free upgrade.

⭐ Better space for orthodontic alignment – Less need for tooth extractions.

⭐ Stability – Unlike nonvascularized bone grafts, this bone won’t shrink over time.

⚠️ The Potential Drama:

🚨 Anchorage issues – If the patient lacks premolars/molars, the posterior teeth might move instead of the maxilla.

🚨 Tooth proclination – If the palatal osteotomy isn’t done properly, the front teeth might tip forward instead.

🚨 Appliance limitations – Tooth-borne distractors provide great control, but bone-borne devices might be more stable.