Orthodontic philosophies, much like those in medicine, tend to swing with the pendulum of trends and innovations. In the medical field, we’ve seen treatments rise and fall in popularity—antihistamines were once heralded as a cure-all, and antibiotics became the go-to for nearly every ailment. Similarly, in orthodontics, we’ve witnessed an evolving landscape of treatments and tools: non-extraction versus extraction approaches, debates over which teeth to extract, and a constant shift between fixed and removable appliances. Each innovation, from square tubes to round tubes and from labial to lingual appliances, has had its moment in the spotlight.

In this article we will explore: What is the role of the extra-oral appliance? Where does it find use? What are its limitations? How valid are the multiplicity of claims made for it?

The use of extraoral appliances isn’t new. As early as 1887, Dr. Edward Angle, a pioneer in orthodontics said “The value of the occipital bandage is, I believe, becoming more and more appreciated, and is especially applicable in this class of cases [meaning maxillary protrusions]. I am using the appliance . . . in my 16th case, and I consider it much more satisfactory than any of the few devices described in our literature on the subject.”

Investigating the Facts: A Study of 150 Cases

In a detailed study of 150 Class II, Division 1 malocclusions, headplates and plaster casts were analyzed to assess the role of extraoral force. Among these cases, 107 exhibited normal mandibular arch form, tooth size, and basal bone relationships. These findings suggest that in many cases, the mandibular arch is not the primary culprit in malocclusion; rather, the anteroposterior discrepancy lies in the maxilla. This raises an important question: Should orthodontic therapy target the maxilla while leaving the mandibular arch undisturbed?

The clinical reality supports this approach. Prolonged Class II therapy directed at the mandibular arch often results in unwanted tipping or forward sliding of the lower teeth. By focusing forces on the maxilla, we may achieve better results, including improved tooth interdigitation, reduced overbite and overjet, and restored muscle function and facial aesthetics.

The Debate Around Extraoral Force

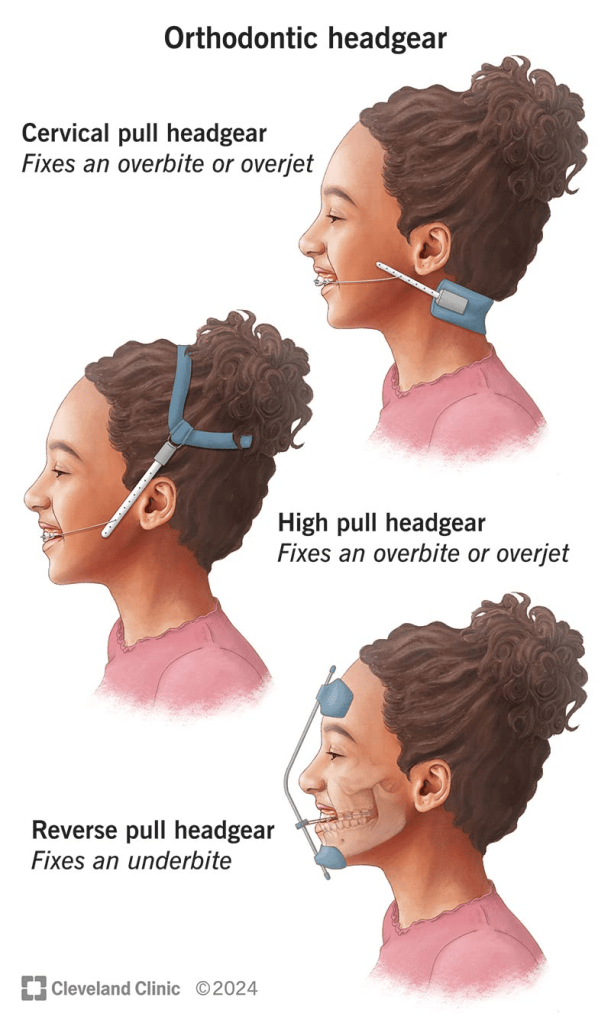

The literature on extraoral force is filled with conflicting claims. Some argue that it restricts maxillary growth, while others suggest it only affects alveolar growth. There are debates about whether it moves teeth bodily or merely tips them, and whether it allows the mandible to grow forward or simply frees occlusal interferences. Even the choice of appliance—headgear versus cervical bands—sparks disagreement.

To bring order to the conflicting claims about extraoral appliances, we must approach the topic with objectivity. What truly happens in a controlled group of cases? Which cases benefit most from extraoral force, and where does it fall short? By critically evaluating both successes and failures, we can better understand the indications, contraindications, and unanswered questions surrounding this treatment modality.

The appliance used consisted of molar bands, an .045 stainless steel labial arch wire with vertical spring loops at the molars, and continuous loops at the lateral canine embrasures to receive the cervical gear. The cervical gear featured a metal tube with a continuous internal spring to provide distal motivating force. In select cases, incisors were banded at certain stages of therapy.

Patients were categorized into three age groups to analyze outcomes based on developmental stages:

- Deciduous dentition: 3 to 6 years

- Mixed dentition: 7 to 10 years

- Permanent dentition: 11 to 19 years

This stratification allowed for a nuanced understanding of how age and dentition stage influenced treatment outcomes.

The study revealed several key insights, supplemented by observations from routine practice where extraoral anchorage was employed in diverse scenarios. These included:

- Bolstering anchorage during full edgewise therapy

- Closing spaces created by distal movement of anterior teeth

- Uprighting individual teeth

- Serving as an active retainer

The study confirmed that Class II, Division 1 cases vary significantly, even when focusing on three core characteristics:

- Maxillomandibular basal relationship

- Overjet

- Overbite

The severity of discrepancies across these factors, combined with patient-specific variables such as morphogenetic patterns, motivation, cooperation, and growth during therapy, made the prognosis unpredictable. Success or failure was influenced by the degree of deviation from the norm in each factor and the interplay between them.

Can extraoral force alone, directed against the maxilla, correct Class II, Division 1 malocclusions?

The goal of establishing normal tooth interdigitation, eliminating excessive overbite and overjet, and restoring muscle function and appearance is ambitious. Achieving these outcomes universally is contingent on numerous factors:

- Hereditary patterns

- Age and sex of the patient

- Presence or absence of third molars

- Growth increments during treatment

- Patient cooperation

Deciduous Dentition Group (3 to 6 years)

- Sample Size: 14 cases, all selected for their severity, characterized by significant basal dysplasias.

- Outcomes:

- Successful correction: Achieved in 3 cases.

- Partial improvement: 3 cases showed near-successful results.

- Residual Class II relationship: Persisted in over half the cases, though to a lesser degree.

- Basal adjustment: Anteroposterior basal adjustment was observed in 11 out of 14 cases.

- Muscle function: Most patients exhibited improved muscle tone and function, along with a reduction in abnormal muscle habits.

- Overjet correction: Often led to excessive lingual tipping of maxillary incisors, especially in cases without pre-existing spacing.

- Overbite correction: The least satisfactory aspect of treatment.

Mixed Dentition Group (7 to 10 years)

- Sample Size: 50 cases (34 girls, 16 boys).

- Outcomes:

- Normal molar relationship: Achieved in 29 cases, though not always accompanied by normal canine relationships.

- Overjet correction: Similar to the deciduous group, excessive lingual inclination of maxillary incisors was noted in some cases.

- Vertical correction: More pronounced and successful compared to the deciduous group.

- Severe discrepancies: Cases with the greatest deviation from normal in basal relationship, overbite, and overjet showed the least favorable results.

Case Examples

- Patient A.L.

- Presented with severe basal malrelationship, marked overjet, and normal overbite.

- Outcome: Immediate and gratifying response due to anterior spacing and lack of excessive overbite.

- Patient J.K.

- Presented with a similar profile but without anterior spacing.

- Outcome: Removal of maxillary second molars facilitated mesiodistal adjustment, resulting in successful correction across all parameters.

Permanent Dentition Cases

- Sample Size: 36 cases (19 boys, 17 girls)

- Growth Correlation: A clear link was observed between the pubertal growth spurt and positive response to mechanotherapy.

- Outcomes:

- 25 patients responded well enough to eliminate Class II characteristics, achieving normal interdigitation and improved aesthetics.

- Success was highly dependent on a combination of favorable growth, patient cooperation, and other individual factors.

Can Extraoral Force Achieve Bodily Distal Movement of Maxillary Teeth?

The ability of extraoral force to influence maxillary growth, move teeth bodily distal, or merely tip them distally has been a subject of debate.

Maxillary Growth

- Observation: There is no evidence that maxillary growth, as governed by sutures, is significantly affected by extraoral force. Claims of growth inhibition require substantiation, which is currently lacking.

- Alveolar Growth: However, maxillary alveolar growth can be influenced. Changes in the anteroposterior apical base relationship are among the most significant findings, as demonstrated by cases like Patient A.M.

Distal Movement of Maxillary First Molars

- Controversy: The possibility of bodily distal movement of maxillary first molars remains contentious. While some authorities categorically deny this, evidence from the study suggests otherwise:

- Cases Supporting Movement:

- Bodily distal movement has been observed in some cases, though it is not the norm.

- Occasionally, this movement occurs unpredictably or can be facilitated by the removal of maxillary second molars during active treatment (Figs. 8 and 9).

- Normal Path Restriction: In most cases, extraoral force restrains the maxillary first molar from moving forward along its natural path or tips it distally.

- Cases Supporting Movement:

Challenges with Tipping

- Excessive Distal Tipping: One drawback of extraoral appliances is the tendency for excessive distal tipping of maxillary first molars.

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Allowing maxillary second molars to erupt before treatment.

- Removing maxillary second molars during treatment.

- Using bands or Rocky Mountain-type crowns on second deciduous molars instead of first permanent molars in the mixed dentition stage.

- Employing a headcap instead of cervical gear, as the headcap is associated with reduced tipping tendencies.

Does Extraoral Force Tip Maxillary Incisors Lingually, Moving Apices Labially?

Yes, extraoral force can cause lingual tipping of the maxillary incisors, with their apices potentially moving labially. This effect is a notable concern in orthodontic treatment, particularly in cases with significant basal discrepancies.

Lingual Tipping of Maxillary Incisors:

- Lingual tipping is a frequent outcome when extraoral force is applied, especially in attempts to correct overjet in cases with marked maxillomandibular basal dysplasia.

- This tipping often results from the inability to fully eliminate the basal malrelationship.

Overjet Correction Challenges:

- Correcting overjet in the presence of basal discrepancies often necessitates:

- Excessive lingual inclination of maxillary incisors.

- Excessive labial inclination of mandibular incisors.

- A combination of both adjustments.

- These compromises are sometimes unavoidable to achieve acceptable occlusal and esthetic outcomes.

- Between the two options, lingual tipping of maxillary incisors is considered the lesser compromise compared to labial tipping of mandibular incisors.

Does Extraoral Force, Directed Against the Maxillary First Molar, Impact Maxillary Second or Third Molars?

The impact of extraoral force on the maxillary second and third molars cannot be definitively answered with a simple “yes” or “no.” However, clinical observations and studies provide insights into potential effects:

Temporary Impact on Second Molars:

- Excessive distal tipping of the maxillary first molars due to extraoral force can temporarily affect the eruption path of the maxillary second molars.

- Once the distal force is removed, the first molars typically upright themselves, allowing the second molars to erupt.

Crossbite and Eruption Issues:

- In some cases, maxillary second molars have been observed to erupt buccally, resulting in crossbite.

- While it is not definitively proven that this is caused by extraoral force, there is a strong likelihood of a connection.

Non-Eruption Cases:

- Four documented cases showed non-eruption of maxillary second molars following extraoral mechanotherapy.

- This suggests that extraoral force may sometimes inhibit the eruption of the second molars, likely due to changes in the eruption path or space limitations.

Impact on Third Molars:

- The diversion of the second molar’s eruption path could also influence the eruption of the maxillary third molars, though this requires further investigation.

Space Limitation in the Alveolar Trough:

- Observations indicate that the alveolar trough may have limited capacity. If space is consumed by distal movement or tipping of the first molars, it may affect the eruption and alignment of second and third molars.

Growth and Timing in Class II Correction

- Importance of Growth:

- Growth is a critical factor in addressing Class II discrepancies. Successful treatment often relies on leveraging the pubertal growth spurt to maximize skeletal and dental changes.

- The maxillary alveolodental complex can be restrained during growth, allowing for a more favorable adjustment of the anteroposterior relationship with minimal reliance on tooth movement.

- Optimal Age for Treatment:

- Girls: Best results observed between 10 to 13 years.

- Boys: Optimal outcomes seen between 12 to 17 years.

- Exceptional cases, such as a 19-year-old boy with significant mandibular growth during a late growth spurt, demonstrate the variability of growth potential.

- Uncertainty of Growth:

- While growth is pivotal, its predictability remains a challenge. The degree of mandibular growth and its impact on correcting Class II malocclusions vary significantly between individuals.

Unilateral Response to Extraoral Force

- Observation of Unilateral Effects:

- In some cases, unilateral response to extraoral force was noted, particularly in the canine region. This posed challenges in achieving bilateral symmetry.

- Contributing Factors:

- Sleeping Position: Patients reported consistently sleeping on one side, which appeared to correlate with reduced movement on that side.

- Chewing Habits: Favoring one side during eating may also contribute to unilateral response, though this remains inconclusive.

- Management Strategies:

- In some cases, a lower lingual appliance was used to provide additional elastic traction, helping address asymmetry. However, unilateral response persisted in certain cases.

Challenges in Achieving Complete Correction

- Residual Discrepancies:

- Even with significant improvement in overjet and molar relationships, Class II characteristics in some segments, particularly the buccal region, may remain unresolved

- Future Considerations:

- The causes of unilateral response and incomplete correction remain areas for further research and clinical focus. Factors such as patient compliance, growth variability, and appliance design must be studied in greater detail.

Does Extraoral Force Free Occlusal Interferences, Stimulate Forward Mandibular Positioning, or Promote Mandibular Growth?

The effects of extraoral force on occlusal interferences, mandibular positioning, and growth remain a topic of debate. The current evidence provides insights but lacks conclusive proof for some claims.

Freeing Occlusal Interferences:

- Extraoral force can alter inclined plane relationships between maxillary and mandibular teeth.

- In cases of mandibular overclosure caused by occlusal interference, combined extraoral force and bite plate therapy can effectively eliminate functional retrusion.

- However, functional retrusions are less frequent and less severe than previously believed.

Stimulating Forward Mandibular Positioning:

- Claims that extraoral force promotes forward mandibular positioning via a neurogenic reflex posture mechanism lack robust evidence.

- While such repositioning cannot be categorically dismissed, it has not been consistently demonstrated under controlled, biometric conditions.

Stimulating Mandibular Growth:

- There is no conclusive evidence that extraoral force or any orthodontic appliance can stimulate mandibular growth beyond the individual’s inherent morphogenetic pattern.

- Apparent acceleration or increased growth rates reported in some studies (e.g., guide planes) have not been reliably duplicated in controlled experiments, such as those conducted at Northwestern University.

Class II to Class I Transformation:

- Eliminating distal displacement through extraoral force does not result in the transformation of a Class II malocclusion into a Class I malocclusion.

- The role of growth and morphogenetic patterns remains the primary determinant of mandibular development.

Challenges and Limitations

- Need for Controlled Studies:

- Many claims regarding mandibular growth stimulation and repositioning remain anecdotal or based on uncontrolled studies. Rigorous biometric analyses are necessary to substantiate such claims.

- Physiological Variability:

- Individual growth patterns, genetic predispositions, and environmental factors contribute to the variability in response to orthodontic treatment.

- Role of Functional Appliances:

- While functional appliances may influence mandibular posture temporarily, their long-term impact on growth remains uncertain.