Intensive microbiologic, immunologic, and morphologic research investigations, especially during the past decade, have shown that colonization of tooth surface by pathogenic bacteria is accompanied by humoral and cellular defense mechanisms of the organism not only during the more advanced stage of infection, but also throughout the initial stages. Penetration of these complex defenses, which is usually of limited duration, disturbs the equilibrium of the system and results in disease. Within the dental pulp, this biologic equilibrium has to do with the balanced calcium and phosphate ion exchange during the continuous demineralization and remineralization of the enamel and exposed dentin. As long as a disease process is reversible, as is incipient caries, the capacity for progression and regression is present. Carious breakdown means that enamel is being demineralized by acidogenic plaque more rapidly than it can be remineralized. In its early stages, the caries has become a chronic destructive process, in which irreversible structural changes will preclude any further remission.

Looking at the dynamics of demineralization and remineralization, and the etiology of caries against the epidemiologic background, and comparing them with the results of therapy, a pattern of active disease spurts alternating with resting phases emerges. During these periods of remission, the chronic destructive process is not reversed, but is only brought to a standstill. This concept of progression and stagnation ( Socransky et al. 1984) is strongly influenced by the defensive capability of the organism.

Progression is defined by invasion of caries into dentin with inflammation and loss of connective tissue. Stagnation means the defenses are increased, there are defensive inflammatory cells in the tissues, and connective tissue is being replaced by secondary dentin or granulation tissue. Histologically, this ever-changing dynamic process in carious teeth is recorded over the years through deposition and destruction of dentin.

For the practitioner, the obvious questions that arise are how to classify the histopathologic condition of the pulp and the apical periodontal tissues, and how to initiate treatment that is appropriate, considering the background of stagnation or progression. Based upon clinical findings, differentiations are made between a clinically sound pulp, reversible pulpitis, irreversible pulpitis, a necrotic pulp, and apical periodontitis. These distinctions are based solely upon clinical observations; generally, a correlation between certain symptoms and a specific pathologic entity cannot be expected. Making the distinction between reversible and irreversible inflammations of the pulpal tissues can be a diagnostic problem, because they can present similar clinical symptoms. Histologically, the diagnosis of acute inflammation is based upon the predominance of neutrophilic granulocytes. However, this diagnostic picture does not always coincide with the appearance of pain symptoms because neutrophilic granulocytes can also be found in cases where there is no pain ( Langeland 1981, Lin and Langeland 1981 b, Lin et al. 1984 ).

DIAGNOSIS OF PROXIMAL CARIES

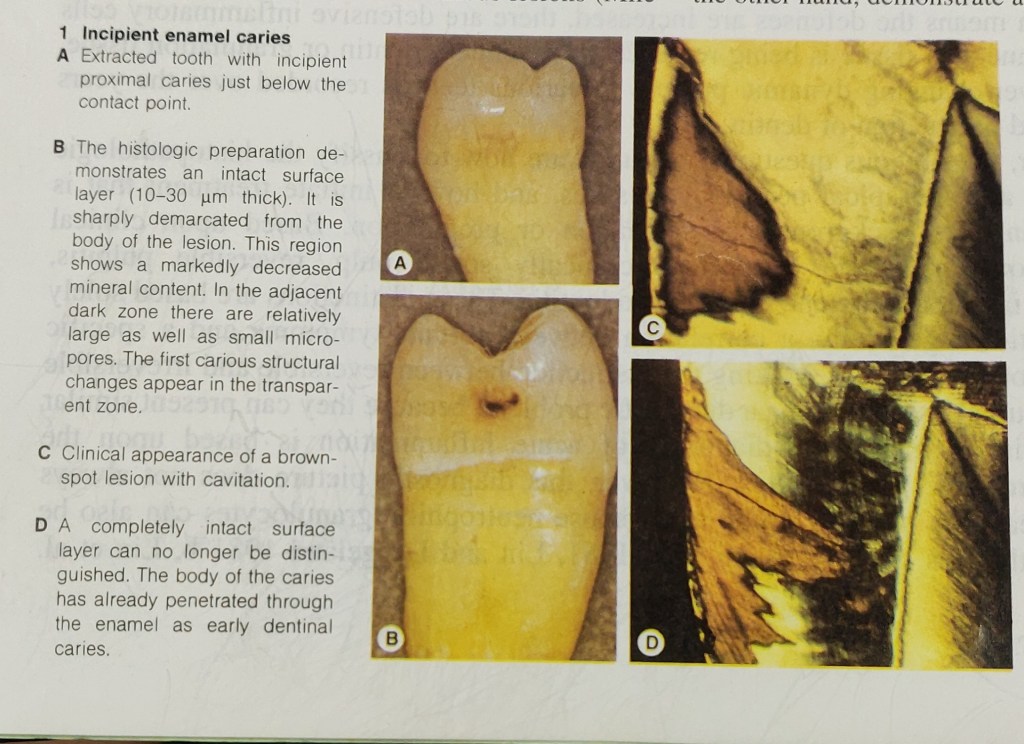

Caries begins with microscopic demineralization of the affected enamel or cementum surface. As it progresses, the enamel first becomes chalky, then its surface is broken through. In this stage, the caries is easy to detect, but has frequently progressed so far that extensive restorative and endodontic treatment in necessary. More difficult to diagnose, on the other hand, are lesions that are in their early stages and dentinal lesions with macroscopically intact surfaces.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that – coincident with a general decrease in caries prevalence in industrialized countries – the occlusal surfaces of the permanent molars of children and young adults are the surfaces most frequently attacked by caries. In contrast to fissure caries, proximal and smooth surface caries is much less frequent. Radiographically evident incipient lesions in enamel of the proximal surfaces have likewise shown a decline. In adults, the probability that these lesions would penetrate further has increased, and this has caused the proportion of proximal caries to rise again.

During clinical examination using explorer many carious lesions with cavity go undiagnosed, so for their proper diagnosis bitewing radiographs, and fiberoptic transillumination (FOTI) are used. Bitewing radiographs are still the method of choice for the diagnosis of approximal caries, and account for the detection of approximately three-fourths of dentinal carious lesions ( Mileman and van der Weele 1990, Noar and Smith 1990). Studies found that where there is a dentinal lesion, there is a surface that has been broken through, which precludes any chance for remineralization (Marthaler and Germann 1970; Bille and Thylstrup 1982; Mejare and Malmgren 1986). Even though the actual extent of caries is underestimated with the radiograph, it may be concluded that the specificity, that is, the ability to recognize sound teeth as sound, is approximately 95% ( Mileman and van der Weele 1990). As far as caries diagnosis is concerned more sensitive X-ray films seem to be the equal of earlier films as far as caries diagnosis is concerned but as they produce same degree of contrast with significantly less radiation, their use is now highly recommended. Preventive measures can impede further penetration and even promote remineralization, provided that the enamel surface has not yet been disrupted.

The progression of caries can be monitored with periodic radiographs. Their interval depends, among other things, upon the individual’s susceptibility to caries. Patients at high risk of caries should be radiographed every year while those at very low risk need only be radiographed every 2-4 years. The time in which it takes caries to penetrate the enamel of a mature permanent molar in a patient with good oral hygiene can exceed 5 years. This offers the opportunity to post-pone invasive restorative treatment and to observe whether the caries progresses or regresses. The rate at which penetration progresses can be estimated by comparing radiographs produced at different times by a standardized technique. Recently erupted teeth, on the other hand, demonstrate a markedly reduced penetration time (Marthaler and Wiesner 1973, Shwarz et al. 1984).

In order to minimize overlapping of the images of approximating tooth surfaces, a film holder is recommended. A deviation of the horizontal angle of the X-ray tube by only a few degrees will result in a substantial decrease in correct diagnoses. Radiolucency in dentin should be treated as invasive only if there is also an unmistakable radiolucency in the enamel region. The radiograph should be inspected carefully under magnification and away from the influence of any light coming from the sides.

FOTI can be used in addition to bitewing radiographs if there is no interference from adjacent interproximal fillings that are other than tooth colored. More than 70% of dentinal lesions in anterior teeth can be detected by means of FOTI. Dentinal lesions in posterior teeth, however, can be differentiated only with great difficulty ( Pieper and Schurade 1987, Choski et al. 1994 ).

Reference – Color Atlas of Dental Medicine

ENDODONTOLGY

Rudolf Beer, Michael A. Baumann, and Syngcuk Kim